When it comes to technology, it’s been an interesting few weeks for our favourite musicians. First there was Twitter’s blue-tick exodus, reducing Beyoncé down to the level of your local binman. Then there was the BRITs revealing its first wave of Billion-Stream award recipients, emphasising the digital nature of our modern consumption. So digital in fact, that we may no longer care if our favourite songs are ‘real’. Welcome to the world of AI musical deepfakes, where fans have been going wild getting artists to sing basically anything that they want them to.

In the name of digital augmentation, several artists have found themselves with particularly unexpected hits. Liam Gallagher quite enjoyed the (Beady)AI version of his Oasis past, while Drake has been struck thrice by the stick of artificial virality: a clip of him ‘singing’ to ‘OMG’ by NewJeans, another of him rapping along to Ice Spice’s ‘Munch’, and an entirely fabricated collaboration between him and the Weeknd entitled ‘Heart On My Sleeve’, streamed well over 20 million times. Universal Records managed to get ‘Heart on My Sleeve’ removed from YouTube and streaming services, but it can still be found circulating across Reddit, TikTok and Twitter, sparking much larger debate about exactly how slippery AI can be with regard to ownership, legality and musical value.

So, how have we even gotten into this mess? According to Dr Melissa Avdeeff, a music and AI researcher at the University of Stirling, there isn’t yet a standard practice for generative music, and creators tend to keep their processes close to their chests. “Generally speaking, though, AI music generators use machine learning algorithms trained on large datasets of recorded music or scores, generating new outputs based on those conventions,” she explains. “Most earlier AI music generators generated music symbolically in the form of a score or MIDI file, but more recent developments can create raw audio files, including human voices, because of their ability to learn and process highly complex patterns. For something like AI Drake, it is likely that the ghostwriter either used UberDUck.AI or similar software; users can input lyrical text that can then be synthesised from a list of available voices. There are a lot of new platforms currently in development, and it’s possible they had access to a beta version of a more powerful platform that is not yet widely available too.

Developing at a speedy rate, it is perhaps no wonder that creativity-seeking fans are enjoying the possibilities of the aural deepfake, a way of fulfilling their wildest stan-collab dreams. Whether it’s imagining a band’s random cover or crafting a set of personalised ChatGPT lyrics in the style of BTS (as a friend recently did for me as a jokey wedding gift), current fan engagements with AI tech seems to come from a well-meaning place, a form of humorous appreciation rather than a sincerely-intended attempt to undercut artistry. And what megafan wouldn’t be curious about the idea of more music from a group that cruelly disbanded too soon? Describing their motivations to create ‘Aisis’ — an eight-track album that layers their own original material with AI-vocals of Liam Gallagher — indie band Breezer explained that it came from the simple impatient desire to imagine what the band’s long-craved reunion might actually sound like. What results is quite uncannily good, with LG himself tweeting a nod of approval: “Mad as fuck I sound mega”.

As the most convincing attempts would suggest, AI works best when it can draw on the analysis of extensive back catalogues, when it involves fairly heavy human intervention, or when it uses singers who have a definitive style that can be pitched or blurred to cover up for any clunkiness. And yet, as Melissa has observed in her early analysis of online fan reactions to musical AI, there is a creeping unease about what this technology might mean. “So far, there are four main themes emerging; copyright issues, the human ‘soul’ of music, the endurance of live music, and the perception that AI is just another production tool,” she says. “Similar to the conversations that have unfolded around AI art, the most prevalent concerns are whether AI tools are stealing from musicians and how copyright will be handled, given that the datasets for new generation are currently dependent on pre-existing recordings.”

Indeed, the case of fake Drake reveals huge problems with copyright law, and the function of the internet in general. While Universal Music Group have put pressure on Google to withdraw fake songs in the name of copyright and artistic integrity, a crackdown on this kind of remix culture directly contradicts Google’s insistence in the value of fair use, undermining their own investments in AI technology and the fundamentals of web 2.0. While Universal were able to get ‘Heart On My Sleeve’ taken down on the grounds that it infringed on the copyright of a Metro Boomin production sample, other artists (especially small-time or emerging creatives) may not be so well-resourced for legal threat.

With regard to more moral codes of conduct, an even further fan conundrum is presented in the case of somebody like Ye. While many might have quite reasonably stepped back from the idea of financially supporting his work, you can imagine a situation where listeners might want to personally justify the use of an AI-generated alternative that offers the same vibe and feel. The morals are dubious, but where the technology offers a loophole, fans are likely to want to take it, especially when the music sounds so close to what you might imagine him to make.

Outside of individual lawsuits and moral cancellation debates, dehumanisation and misuse are already apparent in the way fans are talking about the possibilities of AI, dangling their non-consenting idols like puppets. “What should we make Harry sing next?”, asks one TikTok account, while others appear to be using AI to make artists ‘say’ fake things about new releases or announcements — funny yes, but with dangerous extrapolations for fake news, cancellation and inter-fandom bullying if not appropriately signposted. Given how much personality and vulnerability many artists pour into their lyricism, there is something crude about the way that technology may be seen to supersede creativity and heartfelt emotion, particularly for those who have actively chosen not to engage with social media or technology. We’re already seeing entirely virtual groups emerge out of big K-Pop labels; MAVE, a group put together by Metaverse Entertainment who look and sound alarmingly like aespa, as well as SUPERKIND, a four-piece boyband who boasts an extra AI-generated extra member, Saejin. While the outcomes can be creatively fascinating, they’re also potentially dystopian: if push comes to financial shove, why would a profit-seeking label fund a flesh-and-bone artist when they could sign a virtual alternative who can gig indefinitely without exhaustion, injury or complaint?

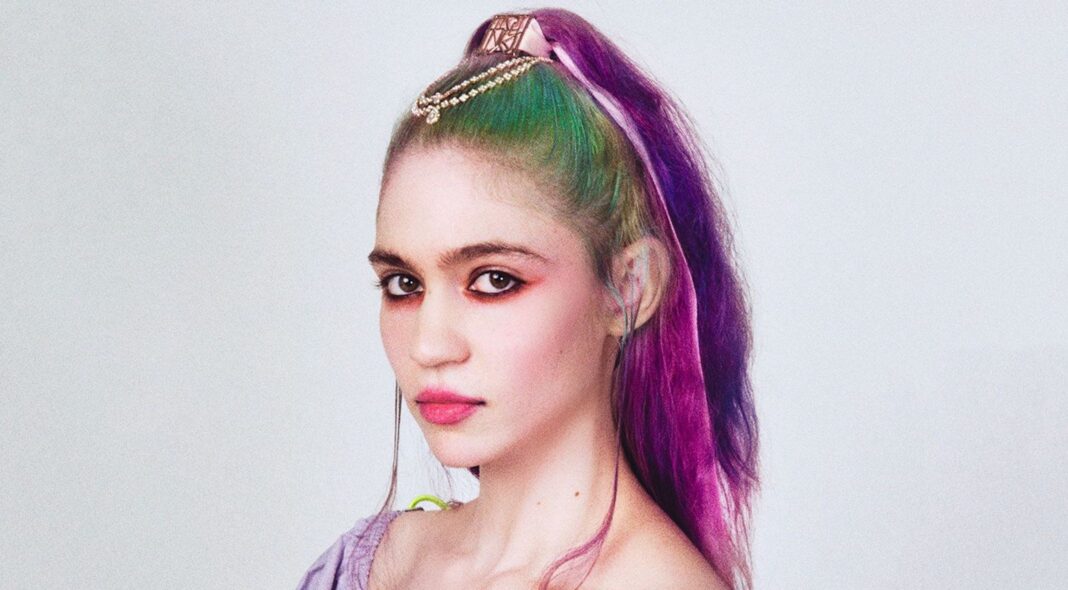

Fortunately, we’re not quite in that place – yet. While ‘Heart On My Sleeve’ or the Kanye freestyle are pretty impressive, they are still rough around the edges, with just enough clunkiness that a keen listener would be able to note the difference. In the same way that a Chat GPT college essay may read OK but be factually inaccurate, AI music or artists still lack the warmth of a human touch, the kind of emotionality that really brings a great song or fan connection to life. Best thought of as an accentuator to art rather than a replacement, some artists are choosing to make the best of it; space cadet Grimes has unsurprisingly been pretty vocal about her enthusiasm for possibilities of AI, actively encouraging fans to remix her voice. But even somebody as experimental as she still seems wary of AI’s potential for fan misuse, warning “no baby murder songs plz.”

With a hard-headed hat on, one might suggest that the popularity of AI only forces artists to either harness this new technology, or work harder to outsmart it. Certainly, the appetite for Fake Drake offers underlying suggestion that his more recent organic work has not been especially inspiring, at risk of easy rip-off. In the same way that torrenting forced us to come up with more legitimised streaming solutions, and streaming forced artists to get more creative with social media and merchandise, AI is in no way without its threats, but it’s a generational shakeup that we may simply have to accept as part of our current landscape. Given that TikTok’s parent company Bytedance is apparently already working on new tools that “significantly lower the music creation barrier and inspire musical creativity and expression, further enriching the music content”, the kind of music generation is very much here to stay, and likely to infiltrate all of our fan platforms. The only question is how openly audiences, artists and industries will choose to engage with it.

“There are a lot of moving parts involved outside of the software producers and musicians themselves, like policy creators and copyright lawyers, that could have huge impacts on what will or will not be possible in the future,’ says Dr Avdeeff. “At the moment, we’re in the first moments of industry disruption, a ‘wild west’ of uncovering what is possible and how we can push our current boundaries. We should be wary of record labels pushing for a complete ban on the use of their music in training sets, but there also needs to be regulations in place that benefit and protect the artists. It’s going to be a difficult balance to achieve.”