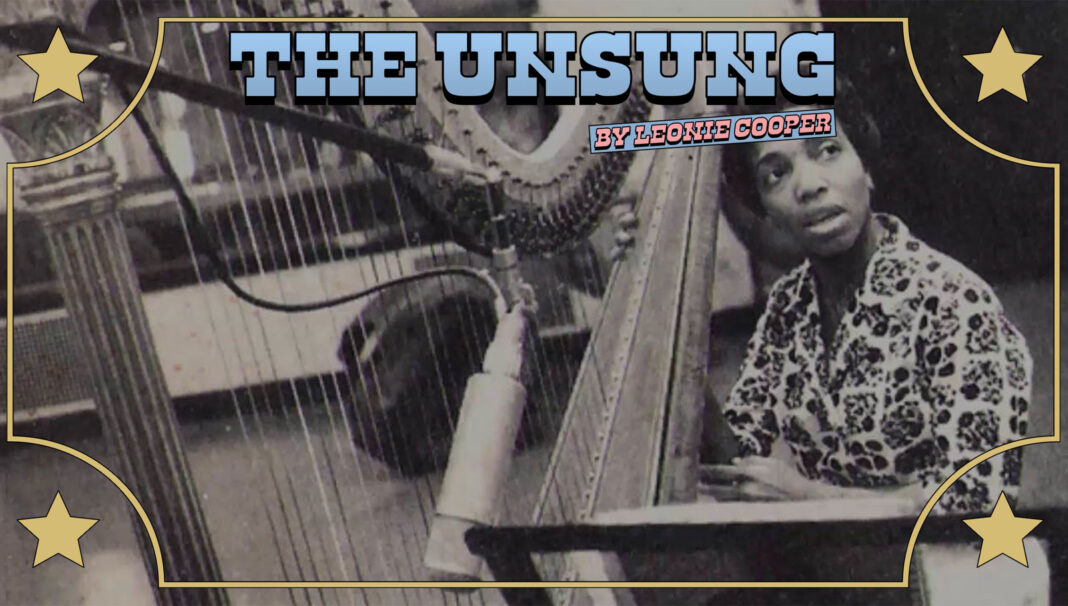

If ‘jazz harp’ sounds like the kind of thing shady government forces would use to extract top-secret information out of unwilling intelligence agents, then you’ve probably never encountered the sublime sound of Dorothy Ashby. A true sonic and cultural innovator, Dorothy lifted the harp out of its classic confines and plonked it firmly in the 20th century.

Born in Detroit in 1932, Dorothy was raised in a deeply musical family, her father – a guitarist called Wiley Thompson – regularly brought home fellow players and as a child she learned to accompany them on piano. At school, her skills didn’t go unnoticed and as a student at the acclaimed Cass Technical High School in the 1940s she developed a fondness for the harp, pivoting easily to the complex instrument thanks to years of experience on the piano.

As the jazz phenomenon skyrocketed in the early 1950s Dorothy quickly became a fan and decided to get stuck in herself. But rather than stick with the piano, she bought the harp along with her. However, this supposedly revolutionary scene wasn’t quite so anarchic. Despite purporting to be open to new ways of doing things, they hadn’t quite counted on the arrival of a woman with a harp. “It’s been maybe a triple burden in that not a lot of women are becoming known as jazz players,” she said in the 1983 book Living the Jazz Life. “There is also the connection with Black women. The audiences I was trying to reach were not interested in the harp, period – classical or otherwise – and they were certainly not interested in seeing a Black woman playing the harp.”

Not that she let this put her off. A forerunner of the far more well-known Alice Coltrane, Dorothy resorted to playing free shows in order to get in front of an audience and show off her innovative take on bebop. “Nobody had ever told me these things shouldn’t be done, or were not usually done on the harp, because I didn’t hear it any other way,” she later said. “The only thing I was interested in doing was playing jazz on the harp.” Her unflattering commitment – not to mention immense talent – developed a following over the decade and allowed her to release her debut album, ‘The Jazz Harpist’, in 1957. Featuring four of her own compositions, including the elegant ‘Spicy’, and three standards, it was a groundbreaking mixture of smooth and unusual, but her best work was yet to come. After a handful more of traditional releases as well as tours with her trio which saw her sharing stages with the likes of Louis Armstrong, Dorothy found herself a staple of the jazz scene, hosting a weekly radio show and becoming a jazz critic as well as running a Black theatre company with her husband John called The Ashby Players.

Then, at the height of the Civil Rights Movement, Dorothy released the definitive ‘Afro-Harping’. With a definite funk influence – opening track ‘Soul Vibrations’ buzzes with the psychedelic groove of Sly and the Family Stone – the 1968 album’s sound was not just one of innovation but of emancipation.

After 1970’s swinging and spiritual ‘The Rubaiyat Of Dorothy Ashby’ – which saw her playing the Japanese koto – she moved to California and found herself the darling of the soul scene and an in-demand studio session player. Collaborating with everyone from Bill Withers to Minnie Ripperton, her most notable guest spot was with Stevie Wonder on ‘Songs on the Key of Life’’s stand-out ‘If It’s Magic’. Though she died at the age of 53, Dorothy’s legacy lives on, sampled by Drake on 2018’s ‘Final Fantasy’ and brought to vibrant life by soul harpist Madison Calley.

Hear Dorothy’s influence in the music of…

Madison Calley

Brandee Younger

Mary Lattimore

The Unsung is a weekly series. Get to know the stories of more musical heroes.

Like what we do? Support The Forty-Five’s original editorial with a monthly Patreon subscription. It gets you early access to our Cover Story and lots of other goodies – and crucially, helps fund our writers and photographers.

Become a Patron!