Just under a year ago, I received an intriguing email from my supervisor at the University where I completed my PhD. I’d been working on a study of fans’ reactions to misogyny in the music industry, and they wondered if I might be interested in sharing some of my findings with the UK Government.

With a few other colleagues, I wrote my piece, sent it off, and didn’t think much about it. With my cynical hat on, I figured that it would probably fall by the wayside, another way to pay lip service to women without properly engaging with their genuine needs. But this week, that report came to fruition. In 74 pages, the Misogyny In Music report hears from numerous women across many factions of the music industry — DJ Annie Mac, X-Factor star Rebecca Ferguson, Primavera Sound’s Marta Pallarés and many more. It concludes, in pretty damning language, what many of us already know; when it comes to discrimination against women, we have an endemic issue on our hands:

“Women working in the music industry face limitations in opportunity, a lack of support, gender discrimination and sexual harassment and assault as well as the persistent issue of unequal pay in a sector dominated by self-employment and gendered power imbalances. Despite increases in representation, these issues are endemic and are intensified for women faced with intersectional barriers, particularly racial discrimination.”

Abuse and misogyny are not unique to music, but when we think about the specific conditions of this industry, it’s almost impossible to fully unpick or capture the real extent of how it feels to be trying to forge a career in an industry that seems determined to suppress your potential. As we have seen time and time again with artists like RAYE, Rebecca Ferguson, Kesha, and even Taylor Swift, female artists have been vulnerable to being held in contracts that don’t serve their artistry, safety, or personal autonomy, or otherwise strung along and let go in moments where they’d already given everything they thought they had to be a success.

It’s also about the smaller microaggressions. The being told you’re ‘good for a girl’, that you must be the girlfriend or groupie for the band, or that your gender can be confused with genre to the point that labels, bookers, and editors see ‘female-fronted’ and assume that’s all you have to give. It’s being a shit-hot writer, promoter or artist and knowing that your achievements will always be clouded by criticisms of affirmative action or nepo babyism, the kind of which rarely raises anywhere near as much vitriol when the person in question is a man. It’s wanting to pursue a career in music production or engineering, but not particularly enjoying being the only girl in the classroom, or being pushed to the front of the ‘diverse’ prospectus photo and then ignored the rest of the time. It’s being pushed to be sexual to sell records, but then slagged off if you’re doing it too much, or not in the ‘right’ kind of body, or with the ‘wrong’ kind of self-confidence. It’s being Black and therefore ‘R&B’, or being introverted and therefore ‘Sad Girl Indie’, dehumanised in endless forms of marketing fetishisation.

When asked about the report on BBC Radio Four this week, Self Esteem noted that regarding the lack of female festival headliners, it takes years to build an artist up to the point where she can reasonably hold that position, and during that time, she has likely quit music entirely. “Plenty of people just deploy logic and leave the industry,” she said. “You are made to feel like you’re being over the top, too much, a princess, a diva. Now, me at 37, reading this report I’m going – well yeah, I feel validated.”

Elsewhere, The Forty-Five spoke directly to other women who cited the report as a thankful moment of recognition, but also a sign of just how deep-rooted the cruelty against women can be. Jay*, a singer-songwriter who preferred to be referred to in this piece via pseudonym, has been in the music industry since she was young. Her first band ended up being offered a record deal, but it came with a caveat; she had to lose weight to fit their “marketable” image.

“I was around nine stone at the time and our male drummer was near the 20 stone mark, yet it was me that was deemed too heavy,” she says. “Having already restricted my eating so much, I felt the pressure from band members, management and the label to take drastic measures and as a result developed a thyroid disorder and heart arrhythmia.” Jay’s drummer ended up leaving to join another established band, and the whole deal fell apart. “Our manager & potential label still haven’t contacted me to this day.”

Harrowed by this experience, Jay took time out of the industry and ended up having children, an aspect of her life that she feels she had to hide now that she is playing music again. “I know I would lose support tours, that my 80% male audience would not want to think of me as ‘taken’ or ‘older’. Competition for women is so fierce and we have to try so hard to be seen & heard in comparison to our male counterparts; I find there is a very real pressure to keep our heads down & not rock the boat.”

Janelle Borg, guitarist of art-rock group ĠENN, tells a similar story, with the “double whammy of being female-presenting and from an immigrant and working-class background.” “We’ve just released our first album [‘unum”] independently, but in terms of gendered barriers, there have been many conscious and unconscious biases throughout the years,” she says. “These include not being considered because there’s already an “all-female band” on a roster, as well as healthcare-related issues such as endometriosis, which are still severely misunderstood and have a big impact on things like touring.

Therapy and having each other as a good support system helps, as well as the vital work that grassroots organisations like Loud Women and Get In Her Ears do to give women and NB folk career support. But people really need to realise that sexism isn’t a thing of the past; most entertainment and music industry gatekeepers are still cis men, and many female and non-binary NB folk are exhausted of constantly having to fight against this behemoth. Some are still afraid of talking publicly about this due to potential repercussions. But if we don’t speak about it, who will?”

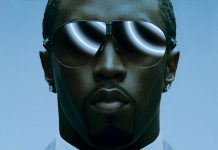

As Janelle alludes, the repercussions that women face are significant, not least when they relate to gendered violence. We’re familiar with the inroads that the MeToo movement had in other industries, but the tangible consequences in music have been far harder to come by, with flagship cases against the likes of P Diddy, R. Kelly and Marilyn Manson only coming about after years of investigation and multiple witness testimony.

In smaller or more local scenes, offending artists often become ‘open secrets’, quietly waiting out a few years before staging a comeback, or else maintaining a fanbase who don’t much care for the allegations or insist that they must be untrue. As the Misogyny In Music report found, the informal environments in which music work takes place means that abuse is upsettingly common, with those who are self-employed or on freelance contracts being particularly vulnerable due to the lack of clear company ‘rules’ or reporting procedures.

And then of course, there are the offenders who aren’t musicians at all, but rather label execs, managers, assistants, PRs, journalists and even fans, able to take shelter outside of the ‘celebrity’ public interest. Outsiders may wonder why it takes women so long to speak up, but they often don’t see the menacing DMs and pseudo-legal blog posts that serve to threaten potential accusers into silence, the complacent attitudes of men who know that even if a whistle is blown they’re still far more likely to hold onto their careers when all is said and done.

“Everyone knows everyone in this industry, and the fear is confiding in someone who ends up being close to the very person who has caused you distress,” says Jay. “Sadly it is hard to know who the good ones are, especially with so many of us not fully able to share our horror stories until it is often too late. It can make things terrifyingly lonely.”

Sometimes, violence comes in the form of more overt, systemic threats, trying to stop women from doing the very work that highlights the truth and scale of misogyny itself. Linda Coogan Byrne is a music consultant and equality expert, known for her work on women’s representation in Irish music. Working with data collective ‘Why Not Her?’, Linda’s quantitative findings contributed directly to this Misogyny in Music report, but she has been harassed many times online for her work, facing rape and death threats as well as “numerous online hackings”.

“One crucial lifeline has been connecting with other women and non-binary people in the industry who have faced similar challenges,” she says. “The power of shared experiences, advice, and collective support creates a formidable force that only emboldens me to continue to take a stand against misogyny.”

For Linda, it’s also important to highlight that women’s inclusion doesn’t simply relate to the people on stage or in the charts. “Women are still fighting tooth and nail for a seat at the table where decisions are made, where careers are shaped, and where the future of the industry is charted out. Until we break down those barriers and let women take an equal charge across the board, we’re only scratching the surface of what true equality in the music industry looks like.”

To look toward change, education is of course the first step. Getting men to understand their complicity — whether that is direct sexism, misogyny and violence or simply failing to intervene when they see it happening — is vital if anything is to truly change, as is getting more women into positions of decision-making power. Practically speaking, the Parliamentary report also suggests a stronger stance on the misuse of non-disclosure agreements in cases of sexual abuse, harassment and discrimination, as well as the creation of the Creative Industries Independent Standards Authority (CIISA), which will serve to enforce greater accountability practices for those who work in management roles. Moreover, the report notes that closer attention must be paid to intersectionality and the way that race, class, accessibility, gender and sexuality interact. As Linda notes, what is the point of claiming inclusivity if you’re only platforming neurotypical white middle-class women, or if no attention is paid to the women behind the scenes?

As a music writer who cares passionately about this industry, I’m proud to have contributed in some tiny way to this report, and I hope that in time, the detailed findings and testimonies of the women who spoke so bravely about their personal experiences will come to mean something, to provide the benchmark from which future generations will hopefully have a safer and more welcoming time. The conversation around this subject is great, but the action needs to come quickly, as the report so succinctly concludes:

“Women in the music industry have had their lives ruined and their careers destroyed by men who have never faced the consequences for their actions… The music industry has always prided itself on being a vehicle for social change; when it comes to discrimination, and the harassment and sexual abuse of women, it has a lot of work to do.”