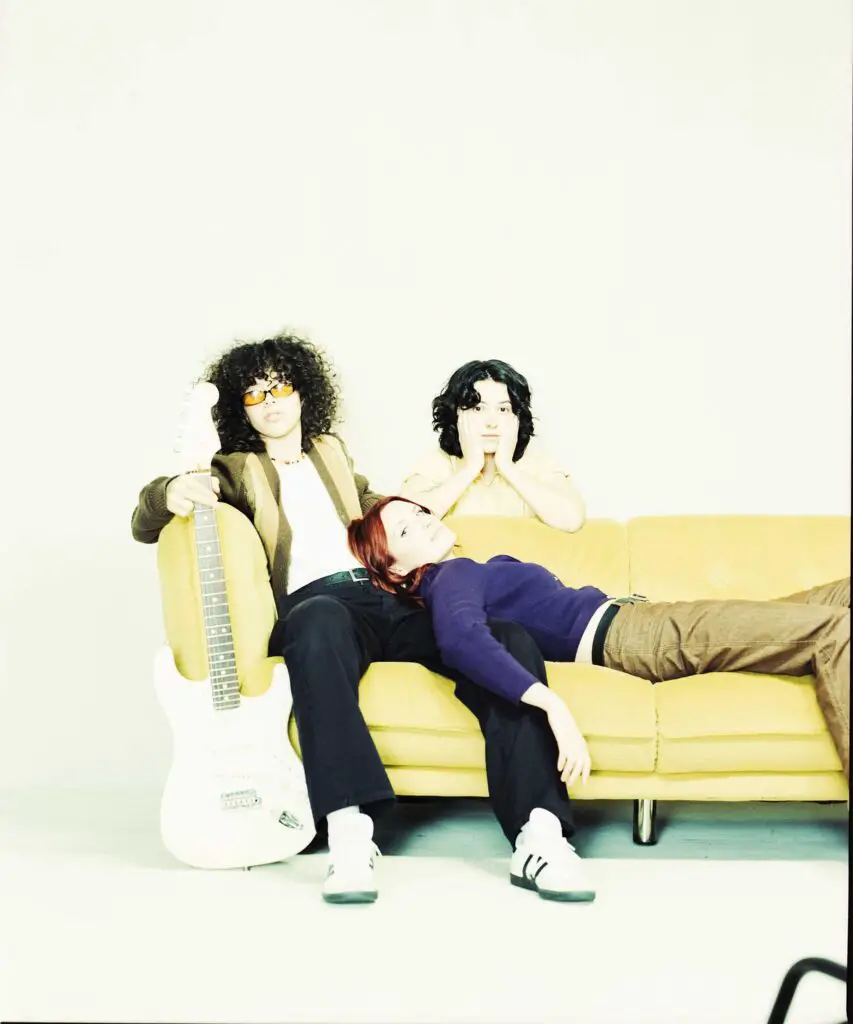

“We’re surviving,” MUNA’s Josette Maskin says optimistically, speaking to The Forty-Five on Zoom just over a week away from the release of the band’s self-titled third album. The LA-based queer pop group, also made up of Naomi McPherson and Katie Gavin, are coming to the end of a “pretty gnarly” run of shows and promo.

The trio’s week started with a performance on ‘The Tonight Show’ with Jimmy Fallon, followed by two nights playing with Phoebe Bridgers in Brooklyn, New York, shows which Maskin describes as “a return home”. When we speak, it’s just hours away from their “massive” Forest Hills stadium show with Bridgers and now-revealed surprise guest Lucy Dacus. “Depressed people unite over our music,” McPherson jokes, referring to the amalgamated fandoms at the trio of shows.

But what the group today lack in quality sleep, they make up for in their graciousness to immediately dive into the candid vulnerability that drives the new album. It’s a record that stays true to the serotonin-inducing highs and intoxicating hooks of MUNA – the kind of music that pushes you to the peripheries of your emotional being, where you’re not sure if falling over the edge looks like running through the streets or crying on the bathroom floor. But as the band are in the home stretch before the release of ‘MUNA’, they now understand their own record better than ever, discovering that downtempo moments like ‘Kind of Girl’, and tear-jerker ‘Loose Garment’ provide the “thesis statement” for the album, whether or not they knew it at the time. “[It’s about] accepting the ebbs and flows of life with regards to how you feel about yourself, how you feel about other people, how you feel about your identity on any given day, or your pain or trauma, and just trying to be gentle with yourself,” McPherson says.

‘MUNA’ is also about learning to have a “good relationship with your pain,” McPherson adds. “I think the album is a lot about agency, and about desire. It feels like trying to grow up and become the adult that you hope to be, and making sure that you love that person.” As Gavin describes it, the joyful moments on this album were “very hard earned”. After all, arriving at a third LP was never a guarantee for the band, who, in mid-2020, were dropped by RCA Records. “Each of our egos were hurt for sure,” McPherson says. “But I think we were going through somewhat of a creative rut and a more emotionally tumultuous period, prior to us getting dropped.” They’ve now made peace with how things turned out. “We were maybe not meant to be in a label structure that large. We maybe needed a bit more attention, and, how do I say this without being gauche? A bit less pressure to have a hit that justifies your existence on the label.” Now working under Bridgers’ Dead Oceans imprint Saddest Factory Records, the band are creatively liberated, though Bridgers does offer practical and creative support, including pushing for ‘Kind of Girl’ to be a single. “She was hellishly right,” Maskin laughs, feigning bitterness.

Pushing through this period of upheaval allowed MUNA to turn out their most vulnerable work yet, without straying too far from what they do best – scintillating sad bangers with euphoric, punch-the-air melodies. After all, music has always been about more for the band, who have known each other since college, than just momentary highs. “What ultimately keeps us together is knowing that someone’s going to hear each one of these songs and use it to make a change they need in their life,” Maskin said in a press statement about the new album. “I think that we made decisions when we were first starting as a band that changed our lives,” she elaborates when I ask if they have always felt this responsibility as a queer band. “You make these tiny little decisions because we [were] just trying to figure things out, and they become so much bigger than ourselves,” she adds. “It’s always allowed us to have a real sense of purpose and to allow our egos to the side.”

When MUNA started out, they deliberated if they even wanted to be an out band. “I do think that we look back on the climate around being out in 2014 versus now, and we’re kind of in awe of how much has changed. And we feel very grateful to be a band that started around that time, because we also feel very aware of all of our queer elders who came before us,” Gavin says. “I simultaneously feel like we have a really, really long way to go.”

Their decision to not only be out but to embrace queerness as central to their identity as a band has proven to be life-changing to fans. “We are privy to so many lovely stories from people who’ve been touched by the music,” McPherson says. Whether it’s inspiring people to come out or work through a mental health crisis, this tangible impact is the “guiding force” for MUNA. Take ‘Silk Chiffon’, their hit single with Bridgers, which they described as “a song for kids to have their first gay kiss to”. The idea of being able to soundtrack to such a pivotal coming-of-age moment draws a strong resemblance to the crucial role that music plays in Netflix’s young adult queer drama Heartstopper, which, as it turns out, the band are huge fans of. “Oh my God, I fucking love that show,” Maskin says. “My girlfriend and I wept the whole time.” And surely MUNA would have been the perfect choice for a sync? “I’m upset that we weren’t to be honest,” Maskin adds. “If we’re not in this next season, I’m gonna riot, because it is one of my favourite shows.”

But while MUNA may appear to be thriving as they prepare for a US and UK headline tour this year, having supported the likes of Harry Styles and Kacey Musgraves in the past, their outward rise isn’t a reflection of the full picture. McPherson recently told Pitchfork that they were “still living on teachers’ salaries”, later posting to Twitter that some had labelled the comment “classist”. But with Little Simz recently cancelling her own US tour due to financial unviability, McPherson’s transparency feels pertinent. “It’s been especially interesting, with the rise of our names, I think people conflate that with economic success,” they say. “I completely echo what Little Simz said. And we can’t afford to do a lot of things as a band right now, even though we would desperately want to.” Gavin agrees: “I think that it’s really important to acknowledge that there are moments in a career as a musician where it helps so fucking much if you do have wealth privilege,” McPherson adds that working in music can sometimes feel like an unpaid internship. “I’m paying for my life with the money that I make from the MUNA stuff right now, and sometimes it gets a little tight in the old pockets.”

But MUNA are promising that their upcoming tour will be “the best show [fans have] ever seen”. They don’t know exactly what that will look like just yet, but they were recently told by Bridgers’ drummer, Marshall Vore, that they perform like they’re “playing a set on Mount Olympus”, which offers a taste of the divine scale they aspire to ascend to. Maskin does make one promise: “People are gonna be dropped to the floor.” Whether it’s in euphoria or anguish, we’ll have to wait and see. But knowing Muna, it’ll probably be a chaotic mix of both.

‘MUNA’ is out now. MUNA will play Bonnaroo 2023