In a Halloween month, as the Phoebe Bridgers adage goes, you can be anything. But whether you’re a witch or a skeleton or the year’s most prominent pop-cultural trend, the very act of dressing up as someone else can bring about some serious existential questions. In thinking deeply about the stories and perspectives and personalities that shape our modern existence, what can be spookier than questioning who the ‘true’ you is underneath it all?

For Halsey, nothing has been bigger of late than the question of life after near death. It has been well-documented that the artist (who uses she/they pronouns) has been processing the aftermath of some supremely harrowing circumstances. In a matter of months in early 2023, she was dropped by her label, began treatment for a form of leukaemia that had only been caught as a result of her diagnosis of lupus, and separated from the father of their baby son, Ender. Withdrawing from the public eye, the idea of a new album presented both a colossal weight and a welcome opportunity, one last chance to explore the truths and creative pathways that may otherwise have been left unsaid:

“I really thought this album might be the last one I ever made,” they said in the album’s launch trailer. “When you get sick like that, you start thinking of ways it could have all been different. What if this isn’t how it all went down? 18-year-old Ashley became Halsey in 2014…what if I debuted in the early 2000s? The 90s? The 80s? The 70s? Am I still Halsey every time? In every timeline? Do I still get sick? Do I become a mom? Am I happy? Lonely? Have I done enough? Have I told the truth? I spent half my life being someone else…I never stopped to ask myself; if it all ended right now, is this a person you’d be proud to leave behind? Is it even you?”

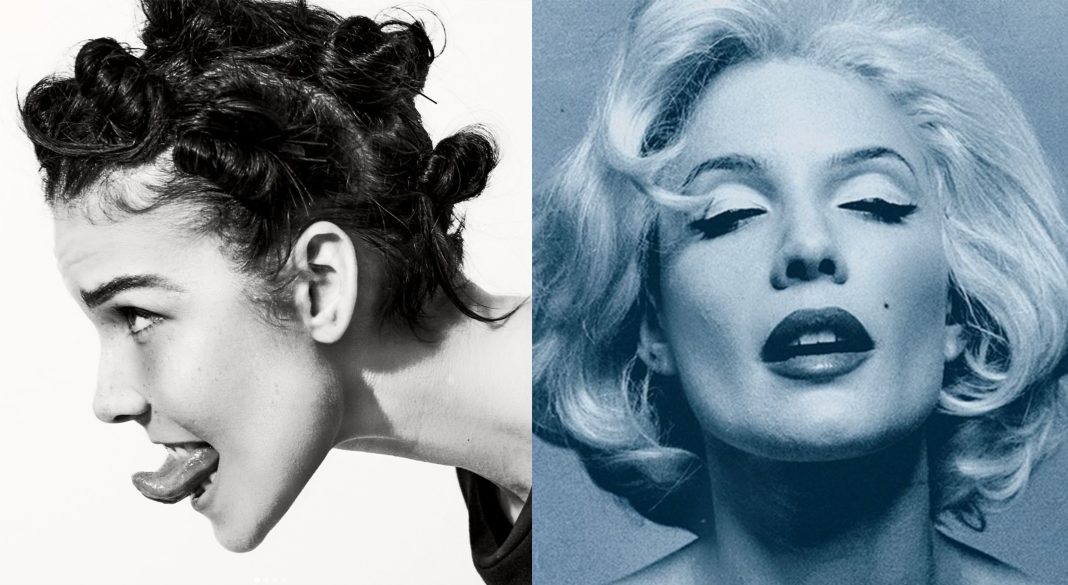

Billed as a ‘confessional concept album’, it was an intriguing proposition that has made for a pretty intriguing album campaign. Over the last fortnight, Halsey has been teasing each track of the new album by cosplaying as the performer who inspired the song. From Tori Amos and PJ Harvey to Amy Lee and Aaliyah, the photoshoots have allowed Halsey to give their flowers to some of music’s boldest and brightest, highlighting the uncanny resemblance that a biracial Halsey has to so many of pop’s iconic women. In the age of AI manipulation and deepfakes, the level of creativity and artistic detail shown by Halsey and the photographer Sarah Pardini truly does feel like something to behold, a loving ode to the shaping voices of Halsey’s pop career.

the photo world needs to be talking WAY more about Halseys marketing rn – for a photographer to be mirroring all these editing styles, all this lighting, all this framing, THIS perfectly & consistently is one of the most insane feats I’ve ever seen. Sarah Pardini is remarkable. pic.twitter.com/s6UbC6w3ft

— holly (@ittybittyholly) October 12, 2024

From the manic pixie dream of ‘Clementine’, to the Madonna/Whore complex of ‘If I Can’t Have Love, I Want Power’, Halsey is no stranger to the embodiment of character in their songs. But whilst some have marvelled at their creativity, others have doubted Halsey’s intentions; including, apparently, some of the women she has paid tribute to.

When lead single ‘Lucky’ was released in July, Britney Spears didn’t seem to massively appreciate the uncanny-valley aspect of its interpolation, stating that she felt “harassed, violated and bullied” that Halsey “would illustrate me in such an ignorant way by tailoring me as a superficial pop star with no heart or concern at all”. While Britney would later retract her comments (“Fake news !!! That was not me on my phone !!! I love Halsey and that’s why I deleted it 🌹 !!!”), it opened the floodgates for a sea of cynical readings of Halsey’s concept, accusing her of name-dropping other people in an attempt to benefit from the marketable affordances of being so closely (and algorithmically) linked to such generational names. Type Halsey’s name into social media and it won’t take you long to see just how many are calling this campaign lazy or cringey or uninspired, more likely to make you remember the greats than to excite you about anything that Halsey themselves is doing. But as always, the proof is in the pudding; as the curtains of anticipation pull away for release day, how does the music actually stack up?

On first listen, ‘The Great Impersonator’ does indeed make a pretty literal interpretation of its source material. Some experiments are more successful than others: the sprinkle of Springsteen, for example, on ‘Letter to God (1983)’, is far more likeable than the nasal twang Halsey adopts for ‘Hometown’, a Dolly Parton pastiche. But once you’ve dug deeper than simply trying to play spot-the-inspo, the sincerity and painstakingly personal lyricism of the record shines through. On the opener ‘Only Living Girl In LA’, Halsey revisits the New York subway stop which gave them their name, crisscrossing between east and west coat in an attempt to reclaim some sense of feeling. Whilst the Cranberries-meets-the-Disney-Channel-2000s angst of ‘Ego’ confesses that “I’m doing way worse than I’m admitting”, ‘I Believe In Magic’ strives to find the strength to seize the day, using mortality and a motivator to spend time amidst the family tree: “roots above and all my branches down below”. Featuring small clips of her son’s chatter and laughter, it’s a love letter to “my little twin”, as well as a touching ode to her mother, watching her advance along her own timeline of life.

Given how complex and detailed some of these lyrics and melodies can be, it’s interesting also that in a recent interview with Rolling Stone, Halsey went as far as to describe some of ‘The Great Impersonator’’s songs as ‘purposefully bad’. It’s rare for an artist to be quite so deprecating, but there is indeed a rough-and-ready quality to the record, a sense of thoughts put down quickly and left broadly untouched. Working with Alex G, most of the music seems designed as a mere canvas for Halsey’s diaristic strengths, blending florid metaphor with lines so plain-stated that they become quite devasting in their childlike truth (“please God, I don’t want to be sick”). The second half of the record is perhaps where things get a bit more energetic: the trip-hop of ‘Arsonist’, for instance, is pegged to the inspiration of Fiona Apple, but blooms into something more widescreen, brooding on the callous nature of an unempathetic partner with whom it takes serious time to become un-entwined. “Your human starter kit came incomplete,” they ponder. “did you ever know the father’s DNA stays inside the mother for seven years?”

‘Life Of The Spider’ meanwhile, billed as the most personal song on the record, is dynamic despite being made up of just trembling voice and piano, using the metaphor of a household pest to summon up the vulnerability of feeling sick and hideous and fearful that those around you will suddenly decide they’ve had enough. “I’m only small / I’m only weak / and you jump at the sight of me / you’ll kill me when I least expect it.” You’d be pretty cold not to feel moved by its fragility, or by ‘Hurt Feelings’, the track where Halsey finally allows themselves to look in the mirror in their attempt to find a muse. Instantly summing up the downbeat electronics of their debut ‘Badlands’ era, its handling of regret, rebirth and the renegotiation of boundaries feels seriously bittersweet, bringing the whole story full circle. That it’s sequenced next to ‘Lucky’ is not a mistake; Much like Charli XCX pulled off with the ‘BRAT’ remix album, it’s fascinating to see an artist be in creative dialogue with themselves, to wrangle with the pressures of fame and celebrity status that has offered them both healing and harm.

In an era where nostalgia sells and content is constantly rebooted or repackaged to simply sell us the same old thing, it’s easy to see where the grumpier takes on Halsey’s concept approach might come from. But with a little time and some generosity of spirit, it’s easy to imagine what this record might mean to people who are feeling adrift, or how cathartic it might have been to make. When you’re sick or lonely or struggling entirely, who isn’t drawn back to the music they loved as a teen? When you don’t know how to feel about a body that is changing through age or sickness or pregnancy or grief, who doesn’t look to those who embody a sense of comfort or courage in the way that they sing, act or dress? Who wouldn’t come close to death and feel compelled to leave something behind that might feel comforting to the fans and family members who loved you the most? In summoning up the courage to explore the biggest act of all — playing at being everyone’s favourite version of Halsey without really knowing your own — The Great Impersonator might not always be musically remarkable or revolutionary. But maybe that’s exactly the point: if facing death means that this era of Halsey is over as we know it, who might Ashley Frangipane be able to become when they allow themselves the grace to start again?