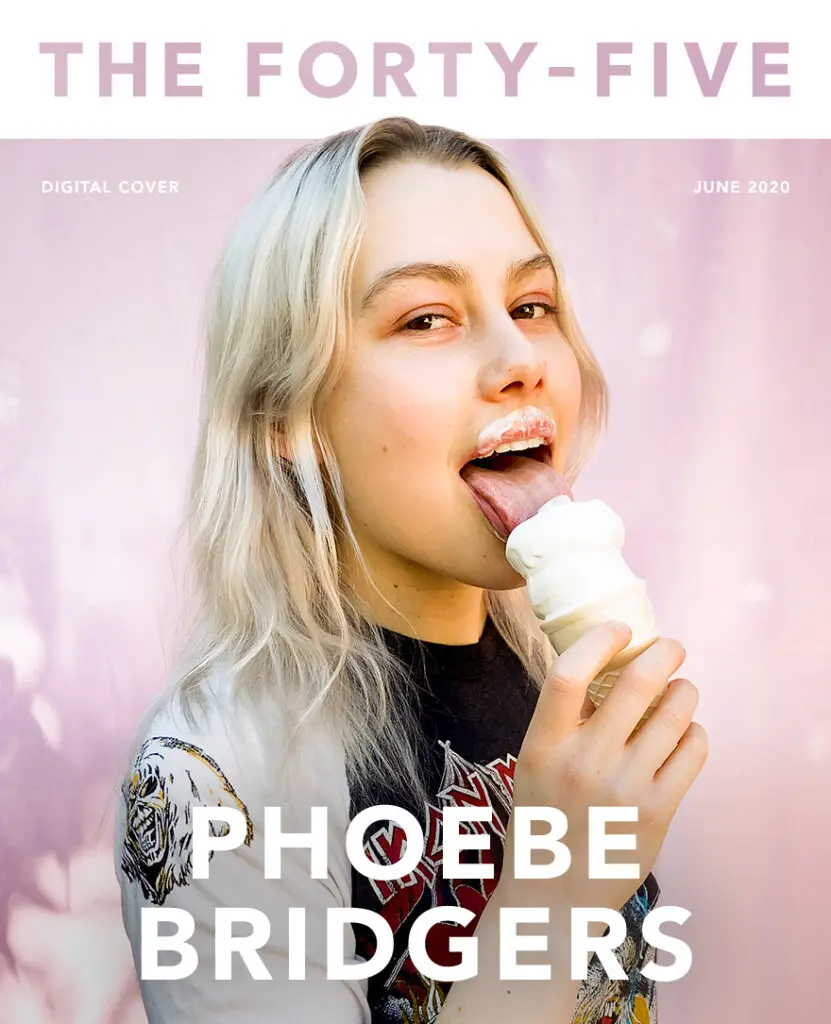

P H O E B E

B R I D G E R S

With her quick wit and devastating lyrics, Phoebe Bridgers has captured a generation. Aimee Cliff meets the singer to talk fangirling Joni Mitchell, her new record ‘Punisher’ and why teenage girls make the best tastemakers.

Photos: Jenn Five. Creative Direction: Emily Barker.

“Every time I finish a song, I feel like I’m done – like I’m out of songs forever.” As with most things she says, Phoebe Bridgers is joking. But as she laughs at her own flippancy on the other end of a Zoom call, with hair still wet from the shower, it’s clear that there’s a grain of truth to the admission, too. In her music, Bridgers is obsessed with endings: she ploughs the depths of grief, break-ups, and the apocalypse for her nihilistic indie rock songs that always feel as though they’re standing on the brink. (“I’ve been playing dead my whole life/ And I get this feeling whenever I feel good, it will be the last time,” she breathes on the vast new single “I See You”.) There’s a sense that she doesn’t take the future for granted.

But, she tells me, she’s starting to gain more faith in herself as a songwriter – and her second album ‘Punisher‘, out this month on indie label Dead Oceans, is testament to why she should. “I slowly started to grow out of [my self-doubt], and realise what my strengths were,” she explains, of the years leading up to ‘Punisher’. She spent that time collaborating with fellow indie singer-songwriters Julien Baker and Lucy Dacus in the band boygenius, and with one of her childhood heroes, Bright Eyes frontman Conor Oberst, as the duo Better Oblivion Community Center. “I felt like having those other bands was accelerated life experience, as far as being a songwriter. If I had not had those two bands, my record would have sounded totally different.”

‘Punisher’ feels like the older, bolder cousin of Bridgers’ 2017 debut, ‘Stranger in the Alps’. Where that album was a clutch of disorienting, sparse indie-folk songs, ‘Punisher’ steps up the tempo with rockier, breezier jams like ‘Kyoto’, and introduces a wider sense of space and experimentation. Bridgers herself co-produced this time, alongside Tony Berg and Ethan Gruska, and in the process learned that “I love taking shit apart and changing the genre, basically.” She had fun sampling an acoustic guitar on ‘Garden Song’ through an iPad, and screaming softly into a microphone for ‘I Know The End’. Even as her lyrics brush up uncomfortably close to the skin, the sonic textures of her world feel brighter, bigger.

As with all album releases since March 2020, ‘Punisher’ is arriving in muted circumstances, with the world placed under quarantine in the midst of a pandemic. Bridgers lives alone in Silverlake, LA, and while she’s naturally accustomed to spending time in her own company, she’s been struggling – like the rest of us – to get anything done amid daily anxiety from reading the news. “I’m like an old iOS,” she says, explaining that she’s been turning to small comforts, and failing to focus on work. “It’s like I accidentally backed up my phone to my old phone in 2011 – except it’s my brain and body. Yesterday I had a peanut butter jelly sandwich for breakfast, and cold pizza for dinner. Which is so not my personality. I keep getting notifications like, ‘Your screen time is up 67%’. It’s hard to be productive and beat off the darkness…” She pauses. “Beat off the darkness. Wow. You can quote me on that.”

YESTERDAY I HAD A PEANUT BUTTER JELLY SANDWICH FOR BREAKFAST AND COLD PIZZA FOR DINNER WHICH IS SO NOT MY PERSONALITY.

PHOEBE BRIDGERS

Much like her Twitter feed, Bridgers is never far from a punchline. Those who write about her music often say it’s counter-intuitive that her social media would be so hilarious when her songs are so sad – but Bridgers is an extremely online millennial, and her tendency for absurdist, dark humour as a coping mechanism makes a lot of sense in a chaotic world. Bridgers laughs, “I’m sure it’ll age horribly, and Zoomers are going to make fun of us.” Early on in the coronavirus pandemic, she met the crisis with tweets like: “I, myself, am non-essential” and “at least america is once again great”. That same barbed tone occasionally cuts through her lyrics – the tender new song ‘Halloween’ opens: “I hate living by the hospital/ The sirens go all night/ I used to joke that if they woke you up, somebody better be dying.” Bridgers’ humour isn’t in spite of her sadness; the two co-exist.

Bridgers grew up in LA, which is “a very pleasant place to grow up because of the nature… But nepotism is so prevalent. Nobody communicates with people outside their circles.” Because of that, she says it would have been easy for her to go down a different route with her music, after she first picked up a guitar at 13, and joined the art-rock band Sloppy Jane in her late teens. “There’s more pressure to monetise [creativity in LA],” she says. “Even when I was 18, I had labels trying to make me act a certain way.” She resisted being moulded by label executives, she says, in part because she suspects she has ADD, and finds it near-impossible to set her mind to anything she doesn’t want to do.

“[ADD] means you can focus on the stuff you love,” Bridgers explains, but not anything else. “Like, I used to play for three hours every Sunday at a farmers’ market, but it was so draining and I hated it. It was hot, and sometimes I just didn’t feel like it, even though I’d make 100 bucks. I was just like, ‘I can’t do it’. Same goes for singing someone else’s songs, or being a pop artist or something.” Even so, she gritted her teeth for long enough to appear in a string of commercials, for brands like Apple and Taco Bell, after being scouted as a teenager. The money she earned from these TV ads gave her the time she needed to write and record ‘Stranger in the Alps‘. “The commercials were easy as fuck, but it also meant that I could be at band practice for five hours the next day,” she explains. “I wouldn’t have had time to make music if I had had another job. It was like I got a grant.”

Bridgers’ home in LA puts her in close proximity to the ghost of her hero, Elliott Smith, who she says would get coffee at the same place where she gets her coffee when he was alive. Though she idolises him, she’s glad that she never got the chance to meet him. His music, for her, has been “a constant, like The Beatles or something. Maybe even more so than The Beatles, because it’s more relatable to me. It’s something I’m never sick of hearing, even though I’ve memorised all of it. Like, I know what his fucking first girlfriend’s name is, I know he moved to Portland because he said he was gonna kill himself if he stayed in Texas. I know his mom’s name, where he grew up. I just know too much about him for us to have a normal conversation. I would punish him.”

This turn of phrase is where the title of Bridgers’ new record comes from: a “punisher” is a fan so obsessive, so intense, that their projections onto the artist they love are too much to handle. Although she’s now met and even worked with some of her heroes (including Oberst), Bridgers is still hyper-conscious of being a punisher herself. When she saw Patti Smith backstage at Carnegie Hall, she remembers, “I could have totally said ‘What’s up’, but I was so afraid I’d punish her that I literally ran away from her.” A similar thing happened when she was introduced to Joni Mitchell. “I actually shook her hand and said ‘Hi’, but I wanted to end the conversation as quickly as possible.”

When it comes to Bridgers’ own fans, while there are some diehards out there (she tells me about her profile on the foot fetish directory WikiFeet, where a picture exists of her feet next to her bandmate’s blurred-out toes, “so that people don’t accidentally jerk off to boy feet”), Bridgers mostly enjoys corresponding with them. She still holds onto her first ever fan letter. There’s one fan in St Louis who she regularly grabs lunch with when she’s in town. “On the other hand,” she reflects, “I once was chased by a full grown adult man from my bus to my hotel, as he was yelling, ‘I would never chase you!’ It’s just, nobody’s the same, you know? People can project all kinds of weird shit onto you.”

Elsewhere on the spectrum, there are the fans who connect to the explicit existential angst of Bridgers’ music, and find themselves talking to her about the emotional issues she’s helped them through. “Sometimes I’m talking to somebody for five hours about suicide,” she says. “It’s a lot of pressure.” Bridgers’ writing style is unflinching, and will often cut to the heart of an ugly emotion by writing vignettes around it. It’s not surprising that her listeners find themselves inside the blue and grey landscapes of her music; she deliberately carves space for them in her writing.

“I can’t write too close to an experience, because I feel like I’ll write a way too sincere, ‘Fuck you for not loving me’ song,” she explains of her oblique, evocative approach to writing lyrics. “But if I’m far enough away from it, I can be like, ‘Oh, it’s way sadder to just describe what’s happening, and not say how you feel about it.’ Almost like JD Salinger or something.”

IT’S WAY SADDER TO JUST DESCRIBE WHAT’S HAPPENING AND NOT SAY HOW YOU FEEL ABOUT IT. ALMOST LIKE JD SALINGER OR SOMETHING

PHOEBE BRIDGERS

A resounding example is ‘I Know the End’, Punisher’s triumphant climax – if triumph can sound like doomsday. The song started life as a break-up song written by Bridgers’ drummer and ex-boyfriend, Marshall Vore, about the end of their relationship. Bridgers took it and blew it up, abstracting the story of their heartache and making it one that’s also about America’s heartache, with a surging, discordant outro powered by brass and screaming. She describes it as a “science fiction” reimagining of a break-up ballad, one in which you can simply drive away and start a new life instead of facing your problems. The references to bolts of lightning, and billboards that say “THE END IS NEAR”, she says are “just political. Like, in the United States, there are still children being detained at the border. I just was like, humanity needs to die. I was just feeling really dark.”

Bridgers’ envisioning of the apocalypse couldn’t feel more apt, given – well, everything. Just weeks ago, Bridgers also appeared on The 1975’s new album ‘Notes on a Conditional Form’, singing on ‘Jesus Christ 2005 God Bless America’, another emotionally cutting song that works on both a personal and allegorical level. Matty Healy has described it as being about the aspects of the US that make him “shiver”. Bridgers says that for her, the song is a “duet, but the people in the duet don’t want to fuck each other. It’s a love song of two lonely people”.

HATING THE 1975 IS SEXIST. TEENAGE GIRLS INVENTED THAT BAND JUST LIKE TEENAGE GIRLS INVENTED THE BEATLES. TEENAGE GIRLS INVENTED MUSIC. YOU’RE TRYING TO SAY SOMETHING’S STUPID BECAUSE TEENAGE GIRLS LIKE IT? IT’S FUCKING INSANE.

PHOEBE BRIDGERS

As a big 1975 fan (even moreso, she says, now she’s met them and learned that the’re “not corrupt and shitty”), Bridgers has found some of the backlash to their new record funny. “Hating The 1975, I feel like, is sexist,” she says. “Because teenage girls invented that band being famous. Like, teenage girls invented the Beatles. Teenage girls invented music. You’re trying to say that something’s stupid just because teenage girls like it? It’s fucking insane.”

The internet in general feels like an angry place to be right now, I say, pointing to the extreme opinions about The 1975 but also recent attempts to “cancel” a slew of female musicians. (“I have not yet been cancelled. I don’t think,” Bridgers muses.) What does she make of seeing this hostility online? “It’s like Julius Caesar or some shit,” she says. “People trying to cancel Billie Eilish is my favourite. It’s just like, you can’t handle how cool she is. Or people saying that female indie rock stars were invented by a trust fund or something. It’s like, you know where The Strokes came from? Nepotism and wealth has always informed music. It has never not. You get more opportunities or whatever, it doesn’t mean that their music is bad. And if we’re gonna shine that light on women, fucking look around at the men whose parents bought them music as a career.”

NEPOTISM AND WEALTH HAS ALWAYS INFORMED MUSIC. IT DOESN’T MEAN THE MUSIC IS BAD.

PHOEBE BRIDGERS

Now is a particularly troubling to be an indie musician, and Bridgers is worried about the impact that the pandemic could have on an industry that already has an entrenched wealth disparity. “I hope middle class musicians survive, because there’s already not enough of them,” she says. “It’s either you have a trust fund, and you can pay to go on tour… You either can afford to not make any money, or you stay in your hometown, you can barely even afford to play gigs. The middle class is disappearing, because there’s such little reward. There’s a danger that [the pandemic will] really increase the privileged divide of music, which is heinous.”

While she’s been reflecting on these fears about what comes next for the music industry, Bridgers admits in an on-brand fashion: “I haven’t been thinking about the future that much.” Just like her music, Bridgers is currently living firmly inside the moment, eating her PB & J sandwiches and making short-term plans for a virtual world tour. In the longer term, she says vaguely, “I would like to write, and record. Those are my hopes. And I hope there’s a vaccine.” While Bridgers makes music for endings, her songs also occasionally glimmer with implicit, trepidatious optimism. On “Garden Song”, she sings, “When I grow up, I’m gonna look up from my phone and see my life.” Even when the future feels impossible, she seems to say, it’s coming. The existence of ‘Punisher’ proves that last time she felt she’d run out of songs forever, she was wrong. Hopefully, she’ll be wrong again.

[…] READ THE FORTY-FIVE’S FIRST EVER COVER INTERVIEW WITH PHOEBE BRIDGERS […]