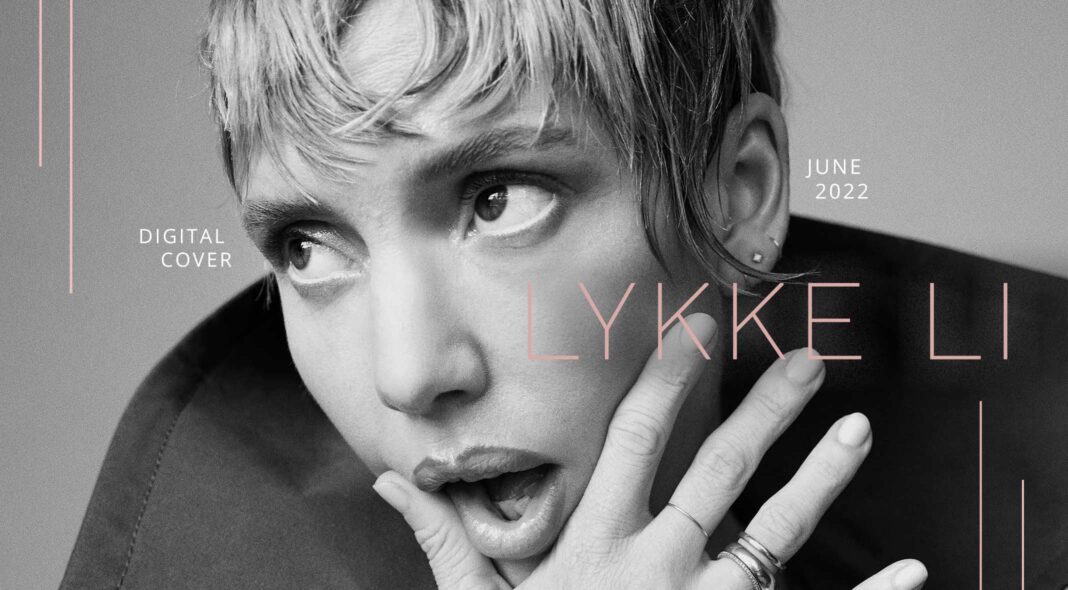

LYKKE LI: BREAKING THE CYCLE

On new album ‘EYEYE’, Lykke Li delivers a final, transcendent blow to her decade-spanning love affair with love. Cordelia Lam meets the heart-on-sleeve artist whose raw emotion is as palpable as ever.

“Love is the most interesting subject of all”, Lykke Li has said in the past. Indeed, love has been the central question at the heart of Lykke’s work for over ten years. Musically, the Swedish singer-songwriter has always been an innovator, dancing freely across genres from indie and folk to pop, dance and trap, but always with a distinctly “Lykke” sound and colour. She sprung onto the mainstream in the early 2010s with indie-pop hits like ‘I Follow Rivers’ and ‘Little Bit’, and in the years since has carved out an esteemed, untouchable position in music with dark, moody, introspective songs cloaked in flawless pop fabric.

Over the next decade, Lykke continued to interrogate that central theme of love, and its dark sides, with fascination. On ‘Youth Novels’ (2008), she explored love and loneliness with wide-eyed, whimsical fancy. On ‘Wounded Rhymes’ (2011), she charted the impossible highs and cavernous lows of volatile love. She packed ‘I Never Learn’ (2014) with “power ballads for the broken”. ‘So Sad So Sexy’ (2018) was a stormy, trap-influenced meditation on sexuality, doomed love, and power.

More recently, in the aftermath of separation, she found herself here, again, drawn to make art out of heartbreak. “I became disillusioned, realising that I was stuck in my own repetition. I had gone through this process of getting my heart broken, feeling extreme pain, then writing music about it, a couple of times now.” Thus emerged her latest, ‘EYEYE’, an album about being caught in the endless cycle of love, heartbreak and art. “I wrote this album from a very broken place. I wanted to make it, for myself, as a final attempt in my battle with love.”

For how much love has hurt her when it goes wrong, “battle” is an apt description. She sings of the endless cycle on ‘Carousel’, a haunting and fantastical melody: “I’m under your spell / Hurts like hell / Oh carousel.” The song’s video counterpart depicts two naked bodies fighting, struggling, tearing at each other, trapped in a red circular room with no exit. The camera spins around, dizzying, as the couple morphs in and out of each other’s bodies. “Watching this repeat enough times, you lose all the technical sensitivity and tap into what the emotion is. It’s obsession. It’s relapse. It’s love,” Lykke says.

I became disillusioned, realising that I was stuck in my own repetition. I had gone through this process of getting my heart broken, feeling extreme pain, then writing music about it, a couple of times now

Lykke Li

Over the years, Lykke has become studied, almost scientific, in her analysis of love. “I’ve always been such a romantic about the idea of it. I see it play out in my head like a movie. But there’s an insight that I’m trying to dissect, about love as an addiction, a neurochemical response.” She built the album around this dissection – “love as attachment, love as a drug, and love as a kind of unreality. When you are an artist and always writing about love, you start to question what’s real versus what’s been created by you in your head. A little bit like when you dream, and all the characters in your dreams are figments of your subconscious.”

The album title, ‘EYEYE’, is a palindrome – spelt the same from the front and the back, a tunnel that begins and ends from the same place. The album’s length, 33 minutes and 33 seconds, is also an ode to this circularity. “The point of ‘EYEYE’ is that it’s a multi-dimensional idea”, Lykke explains. “I wanted to construct the whole album as an endless loop. Being stuck under the influence of love like, it’s a drug.” The album artwork presents Lykke’s face in a blurred, almost unintelligible state. Her eyes are rolled back into her head, her face pallid, trance-like, epileptic. “That’s kind of the album cover. I’m lovesick, out of my mind, drugged up.”

The title is also a product of Lykke’s layered intentions. “The name, ‘EYEYE’, can refer to the third eye, which I looked through to imagine and conceive the sonic world of this album. It can be a place – I think of this album almost like a physical landscape. It could be the name of a drug. It’s also the sound of ‘I’, the self.”

Crucially, the story of ‘EYEYE’ is also told in parallel through film. A stunning video project, directed by Theo Lindquist, accompanies the eight album tracks. Shot on 16mm film, the project is comprised of seven visual “loops”, each a minute long and born out of Lykke’s fascination with repetition. “We wanted to create this hypnotic, trance-like state.” These elaborate vignettes swell with deep reds and blues, heave with sensuality and claustrophobia, and shimmer with neon lights and rainfall straight out of Blade Runner. In the video for ‘Highway to Your Heart’, Lykke is pulled out of a burning car by her love in the middle of a thunderstorm, against the crackle of flame and the burning of metal, calling to mind the attachment, dependency and destructiveness of love as Lykke has explored it.

Lykke has been candid about writing as a means to survive pain and turbulence she has experienced. “There’s a quote that I love: ‘The only way out is in’. That’s very much been the way for me. When I am in a lot of pain and agony, the only way for me to get out is to write about it.” If ‘So Sad So Sexy’ was pulled together from abject chaos (at the time, amongst other things, Lykke had given birth to her son and lost her mother within weeks of each other), ‘EYEYE’ has been stitched together, tearfully and painstakingly, after an apocalypse. After her marriage disintegrated, she faced the unimaginable prospect of putting herself back together from the broken pieces. She poured herself into the project, spending “two years obsessing over every detail and going deeper into the mix than I ever have. It was a very feverish process.”

Lykke’s fixation on the detail culminated in ‘EYEYE’ becoming her “most autobiographical album yet”. This is perhaps most evident on the album’s final song, ‘ü&i’, which chronicles her break-up down to the exact moment in time. “I’m gonna close my eyes / Don’t want to see your back walking / This can’t be the final line / Can’t take this heartbreaking”, she croons quietly, before repeatedly begging her lover to “turn around” for her. “It felt like the song I was waiting to write this whole time. We were actually breaking up like that in real life. Even when you know it’s not working anymore, in that moment all you want is for them to turn around.”

Production on the album was militantly organic, with click-track, headphones and digital instruments exiled from the creative process. “I always work as a reaction to something else I’ve done. When I made ‘I Never Learn’, it was a reaction to ‘Wounded Rhymes’ which had so many drums and very ‘angry’ production. I always want to go to places I haven’t been before sonically, so on this, I decided I wanted to make something very sombre.” The record is earthy and stripped back, with a depth and storminess that transports you viscerally into every scene. The sounds of birds chirping, insects in the night air, car exhaust and reverb from an electric guitar permeate the texture of ‘EYEYE’, mirroring the grounded, soulful way the album was recorded – in the safety of Lykke’s bedroom in LA. “I just wanted to go back to my bedroom, in both a literal and metaphorical sense. It’s where I started at 19 years old, alone with my 8-track and piano, making songs and putting them on Myspace. I recorded the album sitting on the floor, barely showered and with no make-up on. Just myself, no tricks. In the studio, you can be surrounded by engineers and strangers, foreign entities on all sides. Here, I wanted to be as naked as I could.”

Listening back, I can’t even believe I survived what I was going through. It was so intense.

Lykke Li

In the fallout of everything that had happened, Lykke felt the safest delving into the sore points in the trusting, knowing company of Bjorn Yttling, her dearest and oldest collaborator. “Working with him is also very fast,” she remarks. “We’ve spent so many years together figuring out chords and structure; we’re so interested in the song form as a vehicle to take you somewhere. He knows exactly where I want to go, which allows us more time to be in dialogue with the sacred.” Lykke describes their work together as “alchemy.”

“When you make work like this, you are a different person when it’s finished,” she remarks. “The person you’re hearing on this album is a snapshot of who I was then. Making this album was an exercise in trying to paint a portrait of that person in that moment. That’s why I wrote it with such immediacy, as fresh as it comes, my heart pounding and bleeding on the table.”

“Listening back, I can’t even believe I survived what I was going through. It was so intense”, she reflects. She doesn’t keep a diary for such experiences, or even really at all. “I’ve tried, but when I read it back I just thought, ‘My God, this is so depressing. Music is the closest thing to a diary, although sometimes I write myself letters from my higher self.” Talking of higher selves, exploring spirituality and the divine has been profound for Lykke. “My experiences with psychedelics have been so enlightening. I’ve discovered there is always another side to everything. I’m so interested in that duality. Making music is very spiritual, too, when I get into that zone. I also dabble in yoga nidra, a state between waking and sleeping, which has been really amazing.”

Making the album fundamentally changed her, enough that she has moved on a little from the Lykke reflected in ‘EYEYE’. “It was like being pregnant – all the aches and pains of making and holding this piece of art inside, going through this horrible, near-death experience, and turning it into new life.” We talk of motherhood and Lykke’s complicated relationship with this identity. “As a woman, you are constantly thinking about being a mother, even if you decide not to have children. That decision in itself is already an active question that you always have to confront.” She highlights the privilege in even being able to commit herself to creating the album, with a six-year-old son to care for. “Being a modern woman who works necessarily means you have a lot of help. Being able to immerse myself in my work is the utmost luxury and freedom. Even then, you don’t have a second to yourself – your mind is still always with your children.”

“It was like being pregnant – all the aches and pains of making and holding this piece of art inside, going through this horrible, near-death experience, and turning it into new life.”

Lykke Li

We talk about Louise Bourgeois, who she loves, who similarly grappled with a set of fundamental themes for the entirety of her artistic career (betrayal, family trauma, the brutality of womanhood). “Just this morning I read what Tracey Emin wrote about the Louise Bourgeois exhibition in London”, Lykke shares. “The thing that killed me was when Tracey wrote: ‘I would have liked to have had a daughter’. That is the struggle for so many women, who have had to ‘choose’ – you couldn’t be a mother and an artist, because who would take care of the children? I struggled with that a lot.”

Over ten years into her career, Lykke has leaned even more deeply into her power as a lifelong student and soldier of love, exploring the depths of this inexhaustible question from ever bolder perspectives. “I don’t think there’s a time when I’ve known myself more, and hopefully I will only continue to know myself better. And so I set out from the beginning to make every sound, melody and choice on this album only for myself, not anybody else. I wanted to give myself that as an artist.”

‘EYEYE’ is out May 20.

Like what we do? Support The Forty-Five’s original editorial with a monthly Patreon subscription. It gets you early access to our Cover Story and lots of other goodies – and crucially, helps fund our writers and photographers.

Become a Patron!