If you’re old enough to remember Limewire and young enough to have shopped at TammyGirl, you might have taken part in #IndieAmnesty. A hashtag that did the rounds on Twitter in late 2017, it prompted users to share memories of the glory years of landfill indie, a magical time in the early noughties where everything was glowsticks and nothing hurt. Whether it’s the time stuck indoors or a lament over this summer’s cancelled festival season, we’re all on a musical nostalgic kick, and as the hashtag re-emerges in 2020, one anecdote is popping up on the regular: Hackney’s Underage Festival.

Started in 2007, Underage emerged at the hands of teenage promoter Sam Kilcoyne, who was sick of missing out on his favourite bands at 18+ shows. Bolstered by the community of young southern bands at the time (The Horrors, Cajun Dance Party, Late Of The Pier), his string of underage club nights grew from tiny venues in Elephant and Castle into a full day festival event, filling Victoria Park with indie’s best and brightest to entertain 5000 teens aged between 14 and 18.

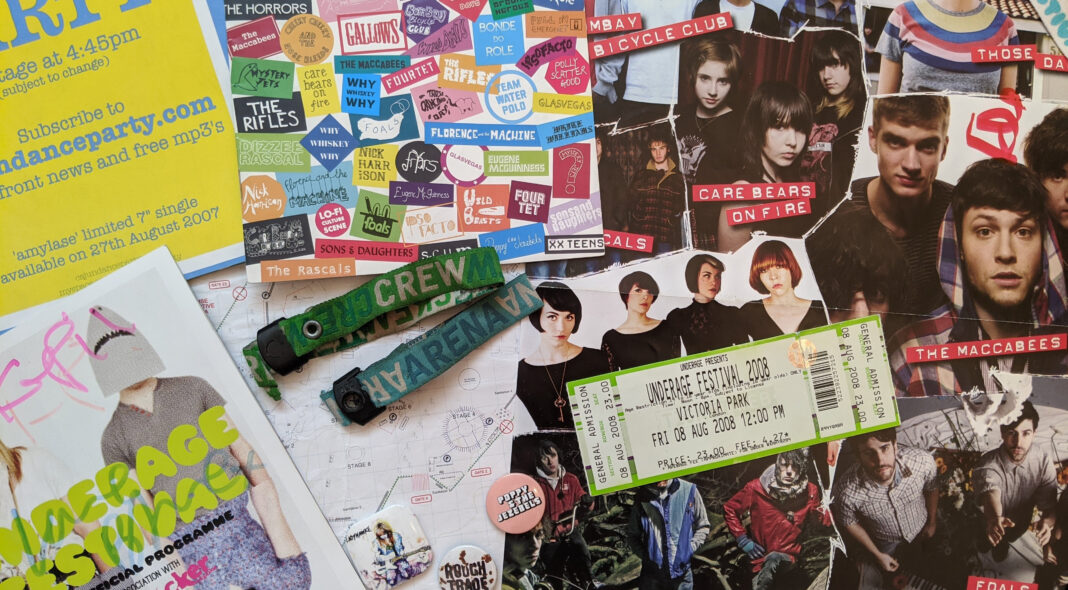

As a snapshot of English adolescence between 2007-2011, Underage was the perfect encapsulation of ‘scene kid’ culture. A good day at Underage meant discovering the new soundtrack to your teenage years, or at least your next profile song. If you were super lucky, you might have managed to nab a blurry selfie with Effy from Skins near the Habbo Hotel stall, or remembered to tie your plimsolls and Topman hoodie tight enough as to not lose them in a Jack Peñate scrum. You might even have squeezed your way onto the MySpace bus, or had your social consciousness formed at the Bollocks To Poverty debate stage. For anyone within that perfect age bracket, it was literal musical heaven – all of your favourite bands in one place, for just over twenty quid, with no parents around to stop you mainlining fizzy sweets or spending way too much pocket money at the merch stall.

Already set on a music journalism career, it was the insight into the world of live music that I had desperately craved, the pages of my favourite music magazines laid out in real life. By 2010, I was 16 and doing work experience backstage, sorting riders and accidentally facilitating a beef between Los Campesinos! and Ellie Goulding for my Tango-sponsored troubles. If this was the height of indie rock and roll, I wanted every part of it. I’d been to arena gigs before, but this was something entirely different – a world populated by teenagers, where anything and everything felt entirely possible.

“It felt like a pilgrimage for me, the first festival I’d ever been to,’ recalls Nick Reilly, now working as a Senior News Reporter at NME. “I still remember that feeling of the walk down from Mile End station to Victoria Park in 2007, surrounded by thousands of other people my age, and then getting in and feeling like yes, this is our thing to cling to. It was sensory overload – watching MIA in 2010, she had these backing dancers who were wearing burkas printed with YouTube logos and at 17, I thought it was the fucking coolest thing I’d ever seen. Tinie Tempah was on that year not long after he’d released ‘Pass Out’, and it was the first time I saw Stornaway who I still love now. Even acts that I wasn’t necessarily a fan of have gone on to do massive things – it’s quite amazing that they got the line up the way they did.”

Looking back on the early bills, it reads like a time capsule of the early noughties DIY scene – Crystal Castles, The Rumble Strips, Hadouken. But as the years went on, Underage showed its commitment to cool in a way that transcended genre. Distinctly ahead of its time in terms of diverse and inclusive booking, the festival’s five-year run accommodated early-years performances ranging from JME to Janelle Monae, Lethal Bizzle to Laura Marling – even a tiny unheard-of by the name of Florence & The Machine.

Flo attracted a modest crowd of young hipsters in floral tea dresses, but her audience paled into insignificance against what can only be known as the Great Sprint of 2008 – an en masse move between Dizzee Rascal on the mainstage and a freshly-hyped Foals, riding high on the success of their debut album ‘Antidotes’. As the tent swelled beyond capacity, the performance was shut down three separate times, organisers begging Yannis to ask the crowd to please stop throwing shoes, climbing masts and trying to clamber onstage. Eventually, they all gave up and leant into the chaos.

“I’ve worked a lot of festivals, and I’ve never seen anything like it – it was like half the site was on fire,” recalls Rich Lucas, editor of Artrocker, which acted as the festival official partner magazine. “I was already way too old to be allowed in the main arena, but I just remember watching from backstage and thinking it looked like the most fun in the world.”

Rich and his team were also responsible for the signing tent – the hallowed onsite space that allowed teens to come into close contact with their indie idols.

“I don’t think any of the organisers really knew what was going to happen when they gave us a basic gazebo and a single table,” He laughs. “Eventually people realised that you could be in the queue and also still see the main stage, so it got even bigger and bigger and really out of hand. We had The Maccabees in and they didn’t even get sat down before the table went flying and they were pinned against the side of the marquee with us who were desperately trying to untie one of the panels to let them out. I remember there was one girl who had a watermelon that she wanted that signing – by the end of the day she had this melon with half the bill on it but no idea what to do with it. It only calmed down when we got The Horrors in: you could see their fans in the queue from a mile off, like they’d stepped out of a Victorian photograph. Instead of the Maccabees riot that we had, we got all these deathly pale goth kids all standing there deadfaced and clapping, just two completely different sets of fans in one field. It was eerie really, but just brilliant.”

Similar scenes of enthusiasm could be found watching Bombay Bicycle Club, a core band for the festival. Playing first in 2008 as teenagers themselves, and then returning to headline in 2011, the carnage they faced belies the somewhat more restrained crowds they are used to playing in front of now.

“I guess these kids just had so much pent up energy – the fact that they had somewhere to go and get all of that energy out was the really beautiful thing about Underage”, remembers Jack. “It kind of became this double-edged sword where we loved how raucous it was, but the inevitable stage invasion would happen and somebody would step on a lead and everything would cut off. I remember being so happy that people were going crazy to our music, and also thinking that we save our best songs till last and never get to play them! You never really knew whether to believe your manager when they were like ‘no, they do it because they’re so excited’…”

“Particularly when we played in 2008, we had just left school, and I mostly remember looking out and thinking that it was probably one of the only times we’d do a festival where the crowd actually looks like the people onstage” muses Jamie, Bombay’s guitarist. “There was this whole scene at that time that came out of the Way Out West label – Mystery Jets, Good Shoes, Les Incompetents, and Cajun Dance Party, who were from our school. Being from North London we weren’t really part of that – we played at Nambucca a lot, which the Holloways lived above, but in truth, our scene was more about just being dropped off by our parents, unloading the gear to play a gig predominantly to our friends before getting picked up again.”

Someone who did benefit from Way out West affiliation was Fred Macpherson of Spector, who appeared at the festival nearly every year in a different incarnation, following on from the aforementioned Les Incompetents. “In that space, there was a lot of under-eighteens stuff – it was a real musical upbringing,” he remembers. “I played at Underage with Ox.Eagle.Lion.Man aged about 19 – we made pretty weird proggy gothy music which went down surprisingly well. I also had a DJ set with my cousin under the name Fisher Price Soundsystem, where we were making everyone play musical statues and having limbo competitions and stuff. Most bands at that time had had more gigs than they’d had rehearsals; it seemed like the most normal thing at the time because it’s all we knew, but I feel for a generation of people now who are into live music and don’t have anything like that.”

Having announced a strong line up that was later cancelled under non-specific licensing issues, Underage’s history came to an abrupt halt in 2012. Somehow, its unceremonious end suits its seat-of-its-skinny-jeans flight to success, a brief moment in time that ended as dramatically as it started. Uniting teens across scenes, it was an event that was both ahead of its time and genius in its simplicity, treating its audience as core fans rather than a non-booze-profit subsidiary.

“For me, it just comes down to the fact that there is a very specific energy in a crowd of exclusively teenagers,” explains Tara Joshi, music editor at Gal-Dem. “I went in 2007 aged 15, and you could feel it wherever you were – the moshpits and people attempting to crowd surf and just going kind of mad. Some acts you could barely hear because the screaming was so loud. You can go to Lovebox or Wireless as a teen but you worry about being too chaotic in case you piss other people off. At Underage, you were all just as giddy as everyone else.”

With more day events available than at the beginning of the decade and most gigs being 14+ as standard, it’s difficult to imagine if the same appetite for an exclusively youth festival would exist today. In many ways, Underage walked so wider age-inclusive events could run. But, still, and especially in light of recent world events, it’s a thrilling thing to imagine a musical event in the hands of today’s teenagers – Gen Z’ers tik-tokking their way through cutting-edge grime and alt-pop, all in on the same shared thrill of new discovery. Music belongs to everyone, but there’s something about being a teenager in front of your new favourite band that makes you feel as if you can change the world. Or at least, makes you feel as if you might just throw that shoe.