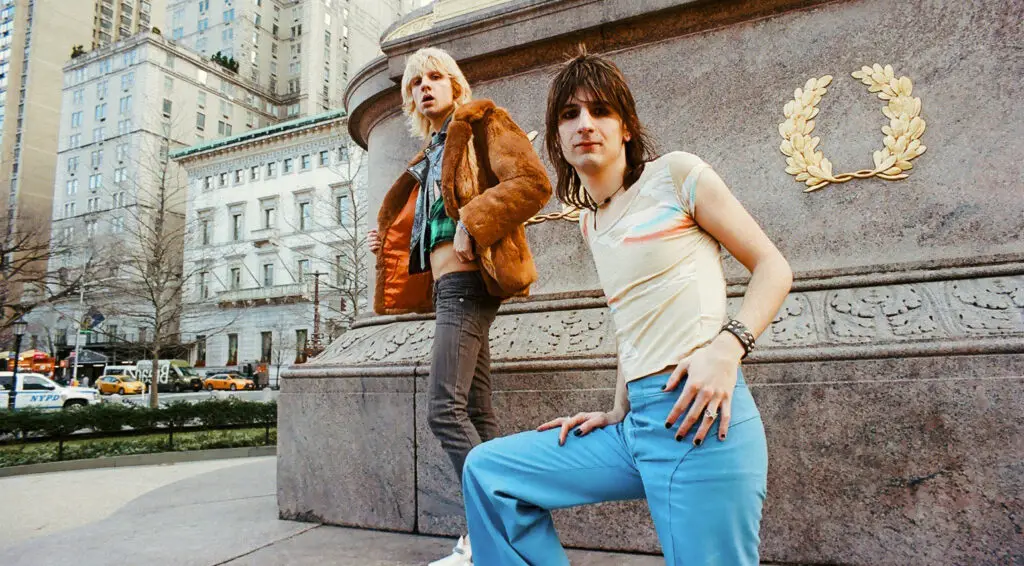

You’d be forgiven for thinking The Lemon Twigs had landed straight from the seventies, emerging suited and booted from a glittery time machine. But they aren’t just stylish imitators. Though the duo – brothers Brian and Michael D’Addario – take lessons in frets and struts from the rock ‘n’ roll greats, there’s not a pastiche in sight: just unbridled talent, a genuine love of all kinds of music, and themes that belong as much to 2020 as to any era.

Be it a showcase of glorious baroque-pop, or a concept record about a chimp that’s actually about the painful joy of being human, the Twigs outgun their contemporaries and give their heroes a run for their money too. New album ‘Songs For The General Public’ is a lyrically brooding yet musically thrilling call to “live in favour of tomorrow”. We caught up with Brian on the phone from New York to talk songwriting, making a fun album in a heavy year, and how it feels to have Elton John as a fan.

Hey Brian! Your first record ‘Do Hollywood’ demonstrated a huge range of genres and musical styles, while your second, ‘Go To School’, had a narrower conceptual focus. This record feels more personal, with songs about love, relationships, emotions. Were you conscious of that while writing?

With the first album, there was so much enthusiasm in showing versatility. After that we wanted to zero in on different styles and attitudes. On this one, our songwriting was hitting a similar place. We wanted to write focused, direct songs. On the first album, we weren’t thinking about the perception of an audience to the lyrics, but with the second one we had to. Now we’re back to a less conscious approach, but because we were used to having the audience in mind, that focus seeped its way into the work. There are definitely a few songs about something I was emotionally past, or I was making it up or exaggerating. That was the process of the second record as well, except with narrative thrown in. But all the songs that expressed emotions on the second record turned out to be my favourite, and the best on the album. That’s generally the place we feel comfortable writing from – one that’s personal, then tweaking things spontaneously.

You and Michael write separately – do you ever come up with songs that are impossible to fit into the same album because they’re too different?

There were tons of songs I imagined would be on this album that we had to push back, because it became something else. Once Michael introduced songs like ‘Hell On Wheels’ and ‘Leather Together’, I had to rethink all these slow acoustic things I wanted to do. And then I wrote things like ‘Only A Fool’ that were more proggy, that fit his energy.

But the way we approach writing in general is different. To me, this album is an extension of the same songwriting principles I’ve been toying with since our first album: following the melody, then finding the feel for the song, but never straying far from the initial intention. With Michael, he knows he wants to do a certain type of song like ‘Leather Together’ and he spontaneously does it really quickly, which is the only way you can do a song like that. The fact he can do something that sounds like an energetic rock band completely by himself is impressive to me.

One of Michael’s songs, ‘Moon’, has more of a Springsteen ‘pulling out of here to win’ feel. Was that a reflection on your hometown?

I’m sure he would say that. It’s very vulnerable and not very tough at all, and there was a period where it seemed childish to him, but I just thought it was a great song. Another of his, ‘Ashamed’, feels very compassionate and sort of ugly but non-judgemental, and to me is an ultimate reflection of Michael’s spirit.

The album’s called ‘Songs For The General Public’. Where did the title come from?

It was the mantra for the album before we knew exactly what was going to be on it. When we released ‘Go To School’ we were telling our managers, “Don’t worry, the next album’s going to be called ‘Songs For The General Public’”. That was always the plan, that set the mood. Of course, I thought there was going to be all those acoustic songs on it, but I didn’t anticipate Michael being into heavier stuff. When we were working on the second record we were writing a lot of direct songs anyway, just to get away from the concept. The new album became all those songs, about things everyone can relate to. There was also a naïve feeling that the album was a commercial version of our sound. When we finished it, we realised our perception of what’s commercial is so off from what’s happening at the moment.

Given the current strangeness of the world, has your perception of the general public changed?

Initially it felt like, man, we couldn’t have a more inappropriate album. If it was going to come out now it should be more soothing than a totally apolitical, fun album about personal relationships that are maybe completely meaningless in the wake of everything. But then, maybe that’s the most fun and meaningful part of life. Everything else is a distraction from personal conflicts, which are microcosms of what happens on a large scale anyway. So I guess my perception hasn’t changed that much. There was a period where I was paying a lot more attention to what was going on from the lens of all these leftist journalists. My girlfriend looked at my Twitter for fifteen minutes and was like, “This is so depressing, why do you do this to yourself?” Because I’m not really doing anything, so it’s completely useless to zero in that much if you’re not going to make it your life’s work. All that was happening was that I was having fights with my dad.

Maybe an “apolitical, fun album” is what everybody needs now.

It’s similar to the idea behind ‘Go To School’ – things were pretty depressing then too – an album that was a fantastical thing that you didn’t want to take seriously. You have to leave your cynicism at home to get inside it.

What was it like recording at Electric Lady, Jimi Hendrix’s recording studio?

We took everything we recorded at other places and put it through the gear there. Jonathan Rado, who produced our first album, booked some time there and left early, and asked if we wanted to go. More than anything, we felt a little silly about having bought all this equipment to have a home studio, because it was so much fun [at Electric Lady]. There’s never been a period where we have to stop recording, so the time limit meant we were working faster and there was more urgency. And the space itself was so cool and sounded so good. But the mythos of it didn’t matter that much to us.

Your sound draws comparisons with a lot of seventies artists. What do you find inspiring about that era?

An ability to fit myself into certain production and songwriting techniques of that time. It’s the way I frame my natural musical personality. It stems from growing up on sixties stuff. Melodically I have more in common with the sixties, but as far as tones and synth sounds go, I love the seventies. It was a great period for recording rock music. I think it’s a lot of people’s favourite because after that more synthetic things were introduced. It was the height of commercial, natural-sounding rock music. But when people ask about influences, I can only think of mid-seventies Cat Stevens – more intricate than his softer, earlier stuff, and more musical.

The record actually reminded me of the Cat Stevens song ‘Sitting’.

Oh man, that was the one I was listening to over and over. That’s a beautiful song. On ‘No One Holds You’ I’m basically doing a Cat Stevens impression.

You often cover the John Prine song ‘Fish and Whistle’ during your shows. We sadly lost him earlier this year. Was he a big influence?

He’s a huge influence. My mum is a huge fan and when I was a kid, she would play him and Tom Waits in the car to show me what beautiful lyrics were. His songs were the first I connected to that were poetic and presented interesting ideas, and where I kind of got it. Everything I was listening to before was British Invasion pop. His music is beautiful. His death felt like a big thing. In the US at least, he’d been having quite a resurgence.

You’ve had nice things said about you by people like Elton John and Gerard Way. Biffy Clyro’s Simon Neil called you ‘the most exciting band this century’. Do statements like that inflate your egos?

We both love it. It’s funny, we have real confidence in the middle of a project, but then towards the end we start to wonder about it. And once it’s done, we really start to wonder about it! If we’re not making stuff as good as we can possibly make it, or as good as the very best, it’s a complete failure. When you’re listening to your own voice, if you don’t think it’s a success artistically, there’s no reason to be listening to it. We’re very aware you can have two or three good albums and then completely be washed up. But you can always discount what others have done too. I asked Michael, “If Harmony Korine [controversial filmmaker] really liked your music would that make you happy about it?” He said; “Yeah I think so.” But I don’t believe it at all.

You’ve got to like it for yourself.

And you probably will only for a relatively short period of time. And that’s good fuel for doing something new.