When I was 14, Topshop was everything. A glossy emblem of all things trendy, I couldn’t afford many of their wares, but it didn’t cost anything to stare lovingly at the rails; the bubble hem skirts worn so effortlessly by Kate Nash and Lilly Allen, the perfectly pre-worn flannels, the rows and rows of colourful plimsolls and pristine leather jackets that instantly granted you membership to the MySpace elite. A couple of quid could immortalise the day out, squeezing into the PhotoBooth to throw peace signs and giggle at the latest ChinoWanker tweets on your iPhone 4, frantically typing out lyrics from the song they’re playing on the shop floor to google it later. 2006-2012 were glorious years.

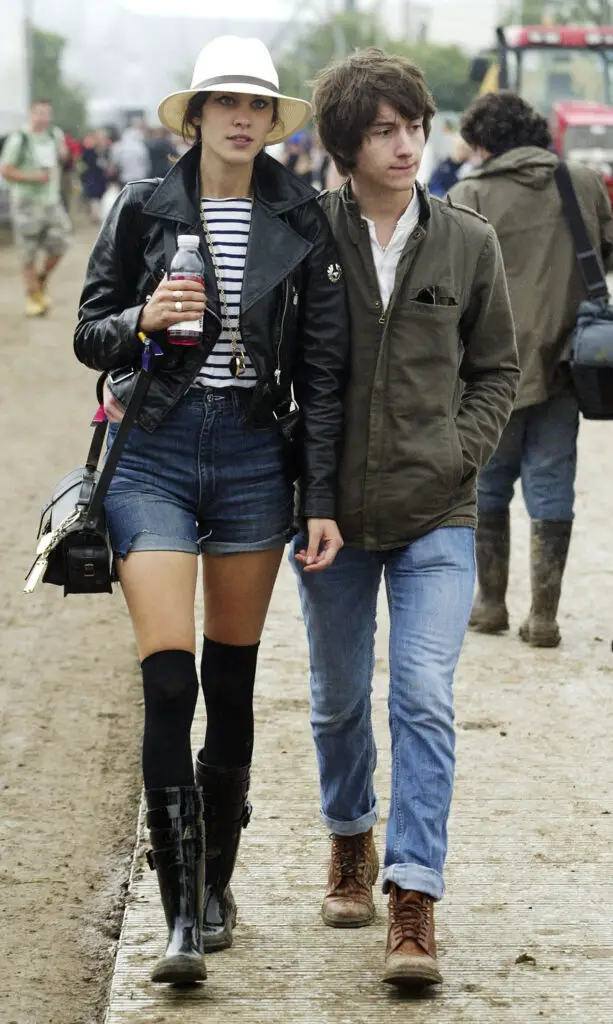

I knew nothing of the politics of fast fashion then. I wasn’t worried about landfill, indie or otherwise. I just knew that Lookbook.nu was life, Alex Turner was the coolest boy on earth and anything that made you look like you were about to get papped at Glastonbury with your arm slung around a member of the Klaxons was a must-wear for the next underage gig in the town over. I was an indie kid through and through, and Topshop was the only place you would want to buy your uniform.

Fast forward a decade and a bit, and both the British high street and the indie music scene look very different. After years of reckoning with a steep financial decline (not to mention multiple accusations of bullying and sexual harassment), Phillip Green’s Arcadia empire (including Topshop, Dorothy Perkins and Burton) appears to be entering the final stages of administration this week, with an estimated 130,000 job losses. It’s horrifying stuff this close to Christmas, but it is endemic of our changing times – consumers who still need fast fashion have had their heads turned by cheaper and more convenient online options, while a broader push for more sustainable and conscious fashion has outpaced anything that Green has been able to provide.

Our music needs have changed too – Spotify and YouTube algorithmic playlists have replaced the thrill of walking into places like Topshop and hearing the latest indie single to change your life for the very first time. Bands cottoned onto this quickly; everyone from Arctic Monkeys to The Holloways and Art Brut found ways to weave Topshop into their lyrics as a catch-all indication of a certain type of youth. From the musical elite sat front row in their fashion week showcases to the now-infamous Rihanna T-shirt lawsuit or first IVY Park launch, they were a brand for whom music was an intrinsic part of both the shopping and marketing experience, and there was a not a noughties trend from emo to chillwave to hipster RnB that they didn’t attempt to provide clothing for. They were also one of the first brands to really harness the power of bloggers, paving the way for influencers like Liv Purvis (still a fashion fave) who have long championed an affiliation between music and style through impeccably curated outfits.

Somewhere in recent years, that trick has clearly worn thin. Maybe it’s a good thing; as fans become more inclined to multi-genre music fandom, the removal of sartorial gatekeeping around certain subcultures will certainly put less of a burden on both wallets and superficial judgment. We’ve all grown a bit savvier to the ‘must-have’ item of the week and are a bit more likely to make up our own mind when it comes to deciding what looks cool. But I do wonder if the teens of today miss out a little by not having those physical, free-access retail spaces in which to enjoy such a key role of adolescent socialisation and identity discovery. Would ‘festival fashion’ have ever grown to the noughties heights it did without Topshop’s key role in the iconoclastic status of Kate Moss and Alexa Chung? Could Nu Rave have even happened without the easy access to skinny jeans and neon hoodies with geometric print hoods? Where are today’s teens going to go to eye up the LEGO-haircutted sixth-former behind the till who is cool enough to be in four local bands? What are they going to carry their PE Kits to school in?

Maybe it’s simply the rose-coloured #indiemanesty glasses talking (non-prescription, obvs), but I’m going to miss Topshop. Not so much the tiny sizing range or the cheaply made garments that fall apart just as quickly as ‘Nintendocore’ record deals. But the idea that by walking into those doors, you were walking into an extension of the music venue, a space where an oversized hair bow, ugly plastic necklace or a long-saved-up-for pair of buckled sandals could give you the confidence of a particularly precocious Skins character. When you’re not old enough for the club and too rambunctious to want to hang out at the hushed record store, where is there left to go IRL to feel that type of cool? It’s a tough thing to answer, and it’s only going to get tougher as more and more things fall victim to the changing passage of time. Gen Z-ers, you have my sympathy and my slew of second-hand flower-crowns and too-short pinafores that will be making their way to eBay as I realise just how old I now am. I hope you enjoy them as much as I did.