Content Warning: Sexual and Physical Violence

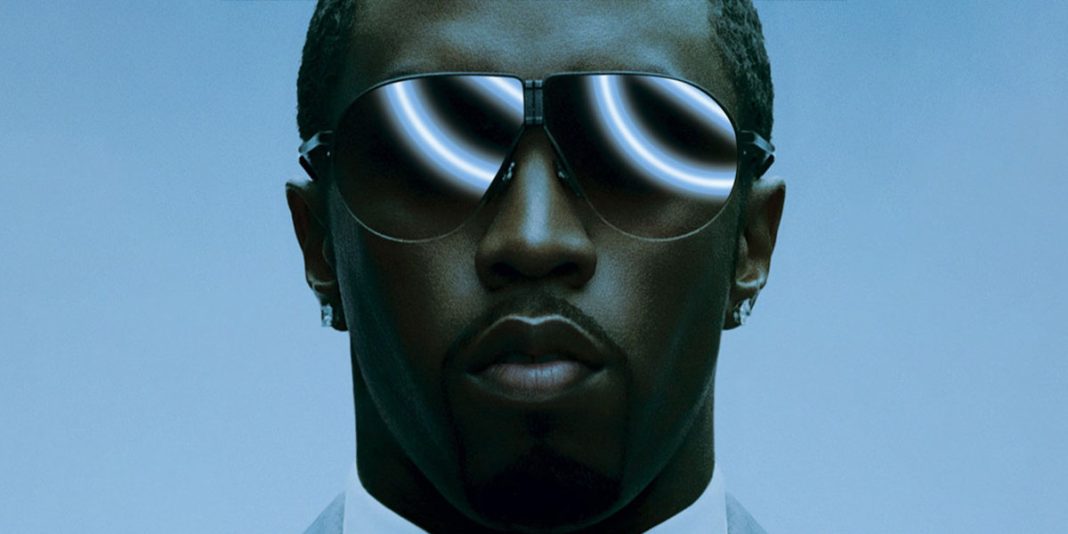

Since November 2023, the rapper, manager and overall music manager known as P Diddy (aka Sean Combs) has been subject to a series of lawsuits, accusing him of sexual assault, sexual trafficking and various other criminal activities. Despite claims of his innocence, the evidence has been compelling, piquing publicly in May with the distribution of video footage of his violence against the pop singer Cassie in a hotel lobby from 2016.

Last week, however, things appear to have come to a new head. On Tuesday 17th, Combs was arrested, and the decision was upheld to keep him in custody without bail. Aside from an earlier apology in response to the Cassie video, Combs denies any wrongdoing, but the unsealed indictment presents a litany of detailed and disturbing allegations of serious and violent crimes: sex trafficking, interstate transportation for purposes of prostitution, coercion and enticement to engage in prostitution, narcotics offences, kidnapping, arson, bribery, and obstruction of justice. If convicted, Combs could be looking at a minimum of 15 years in prison.

Stating that Combs had physically and sexually abused her for the duration of their 11-year relationship, Cassie settled her lawsuit with Diddy the day after it was filed, citing her desire to resolve the issue in a manner under which she still had “some control”. Having made her complaint under the quickly-expiring New York Adult Survivors Act, her courage as a whistleblower cannot be overstated. Since November, Cassie has reportedly been joined by the testimony of 50+ others who can corroborate Combs’s violent behaviour, either as victim or witness.

Just last week, Dawn Richard — a former member of Danity Kane, the girl group that Diddy assembled on MTV show ‘Making The Band’ — alleged that he groped, assaulted and imprisoned her, threatening her life when she tried to intervene in Cassie’s defence. In response, Diddy’s attorney stated that Dawn had “manufactured a series of false claims all in the hopes of trying to get a pay day.” Other lines of defence have been very similar, maintaining an image of a man whose sexual appetites are being unduly criminalised by people who do not understand a rapper’s lifestyle.

In some ways, this reaction is unsurprising. Head of Bad Boy records, Diddy has long been an emblem of hip-hop hedonism, a person who makes careers happen and keeps the party going at all costs. For hip-hop fans, enjoying this kind of music often means turning a blind eye to casual misogyny and the positioning of women as collateral damage in the quest for personal gain. Both Diddy’s lyricism and the lyricism of many of his collaborators has been known to celebrate feelings of sexual ruthlessness, with both empowering and problematic connotations.

However, being sexually adventurous is very different to manipulating power in non-consensual ways. One of the most disturbing details of the Combs’ indictment is evidence that he organised regular “freak offs”, in which female victims were forced and threatened to perform extended group sex acts, lasting multiple days and often on tape. Diddy/Combs is accused of distributing a variety of controlled substances to ensure victim compliancy, and it is alleged that numerous members of the “Combs Enterprise” — supervisors, security and household staff, assistants and other employees— were involved in booking hotel rooms, arranging travel and giving Combs cash to pay sex workers.

As the indictment reads, “Combs maintained control over his victims through, among other things, physical violence, promises of career opportunities, granting and threatening to withhold financial support, and by other coercive means, including tracking their whereabouts, dictating the victims’ appearance, monitoring their medical records, controlling their housing, and supplying them with controlled substances.“

The breadth, detail and dexterous calculation of Combs’ alleged behaviour, tracking well over a decade, draws obvious comparisons to the case of R Kelly, despite Diddy’s defence team stressing that all freak-offs involved “consenting adults” rather than minors. Much like when the Kelly case was revived in the light of the #MeToo movement, numerous think pieces have questioned why these watershed examples of abuse take so long to become public, and why they change so little in the wider music industry. Other genres certainly aren’t innocent; you only need to look at the rampant sexism in emo, pop-punk and lad-rock to note that women are suffering right across the spectrum of musical participation. But there are certain standards in hip-hop that seem to allow things to be both highly public, and strangely under the radar in the court of public opinion.

The first issue, it seems, is money and status. Whilst indie and mid-tier pop musicians often present with some degree of social consciousness or down-to-earth-ness, rappers and hip-hop moguls — particularly those at Combs’ level — are emboldened to become larger-than-life characters, creating a wealth-accumulating orbit around them where unusual behaviours or interests are quickly portrayed as eccentric rather than abusive. That level of power is both terrifying and alluring; it keeps people silent, but it also encourages audiences to focus on the glitz and glamour instead of any more sinister signs.

While hip-shop fans can and do form close social contracts with their idols, the moral expectation that surrounds rap artists — particularly male ones — is also different. In the same online spaces that we endlessly debate the role model responsibilities of artists such as Taylor Swift or Chappell Roan, rappers are given way more space to be mysterious, or to re-brand their controversies as evidence that they do things ‘their way’. For fans who are harbouring certain forms of racial bias or class-cultural exoticisation, hip-hop-based ‘scandal’ can even be viewed as entertainment, in line with growing interests in true crime and voyeuristic online gossip. When we acknowledge hip-hop’s dominance of non-white participants, we must also reckon with the fact that society is incredibly blasé about protecting Black women, or getting involved in “Black people’s business”. Just look at the recent Kendrick vs Drake rap beef — what does it say that mainstream audiences were more concerned about crowning a musical victor than we were about some of the deeply disturbing things said in the songs?

In an age where the outcomes of sexual assault cases are susceptible to the influence of social media (if they end up in court at all), the way that fans and audiences mock, trivialise or excuse allegations can have serious knock-on effects. In my own academic research on the subject, these are the questions I’m constantly pondering, asking what the role of journalists and fans is in the case of artists who are accused of very serious crimes. I’m not necessarily claiming that fans should be responsible for the level of soul-searching work that is better served by the collaborators, managers, associates, and staff who wilfully enable dangerous celebrities, or otherwise don’t feel safe to publicly call them out. But I am an advocate for staying attuned to signs of double-standards, and for recognising that all forms of abuse have to be taken seriously if we’re ever going to get to a place where silence or bad-taste humour isn’t the dominant music industry response.

The coming months are going to be deeply difficult for Sean Combs’ survivors, for his seven young and impressionable children, for fans who wanted to believe that his persona was only an entertaining act. But hip-hop has long been awaiting it’s #MeToo moment, and if taken with the seriousness it deserves, this case has the potential to become the start of positive, as well as an important, long overdue end.