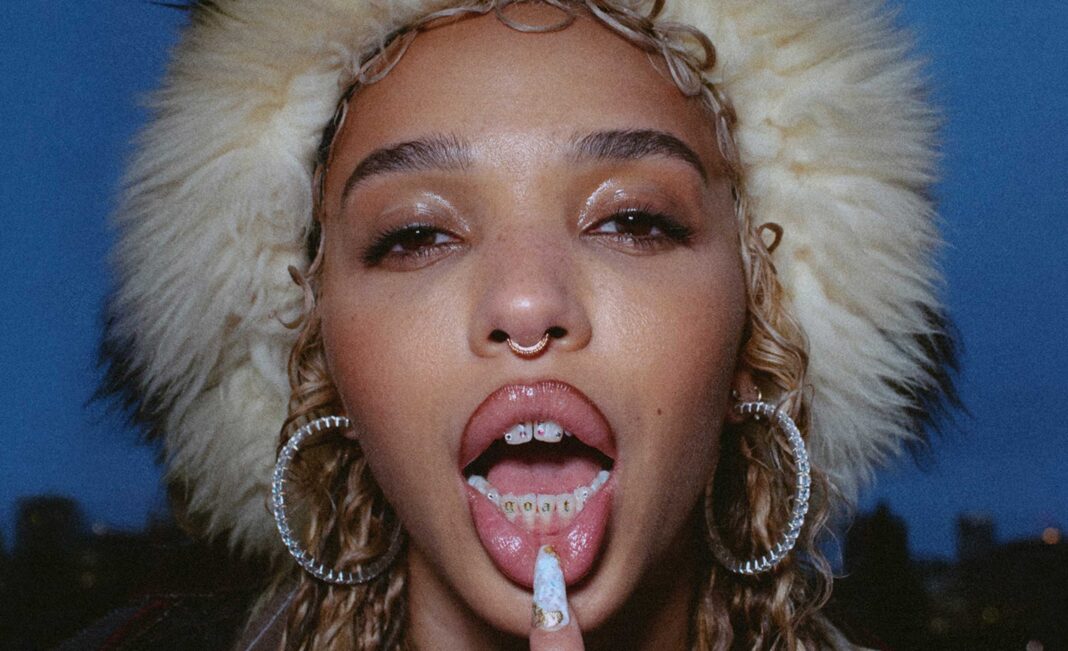

Earlier this year, “the rockstar girlfriend aesthetic” became popular on TikTok, positioning women in relation to an (often male) partner’s music career, through images of leather jackets, dark eye makeup and electric guitars set to rock songs. In the outro to FKA Twigs‘ track ‘which way’ – which features London-based Dystopia (whose members are all women of colour) – Twigs states, “I’m the rockstar, not my boyfriend / I’m not the rockstar’s girlfriend / I am the rockstar girlfriend.” Here, FKA Twigs defines herself by her artistry rather than another person, centring herself and her role as a musician when she elaborates with, “I’m not the accessory to the rockstar, I’m the rockstar.”

FKA Twigs, along with many other female-identifying artists this year, used their music as a way to push back against established narratives surrounding women and rewrite their roles. These were responses to the age-old societal pressure that women face to get married, start families and to behave a certain way, but they’re also the products of women artists having to create spaces for themselves in what is still a male-dominated industry. These artists were able to flip the script, and deconstruct gendered stereotypes, refusing to be boxed in or defined by anyone else.

Taylor Swift details some of those expectations for women across her latest album ‘Midnights.’ On ‘Vigilante Shit,’ she outlines how women are supposed to act: “Ladies always rise above / Ladies know what people want / Someone sweet and kind and fun.” It’s exactly the opposite of how the revenge-motivated protagonist (or maybe more of an ‘Anti-Hero’) behaves during the song, which is why she follows up this description with: “The lady simply had enough.” That final line doesn’t only reject the gender role, but shows how the burden placed on this particular woman is what made her decide to act in contrast to it.

On ‘Lavender Haze’ – a song that deals with public discussion of Swift’s relationship – she talks about how women face pressure to get married. Swift sings, “All they keep asking me / Is if I’m gonna be your bride,” – even a woman of Taylor Swift’s talent and achievements is still ultimately reduced to someone’s wife. Swift evokes the Madonna-whore complex in the following lines, “The only kinda girl they see / Is a one night or a wife,” But Swift rejects this label, specifically the typical “1950’s housewife,” in the chorus when sings, “No deal / The 1950’s shit they want from me.”

‘Midnight Rain’ also depicts a woman deciding against marriage, this time in favour of her career. Swift sings, “He wanted a bride / I was making my own name / Chasing that fame,” flipping around traditional gender roles so that the male love interest is thinking about marriage while the female protagonist prioritises her career. It’s a tradeoff that works, most of the time: “And I never think of him / Except on midnights like this.”

Florence + The Machine discuss a similar choice, this time between family and career, on ‘King’. It opens with: “We argue in the kitchen about whether to have children / About the world ending and the scale of my ambition.” Through their placement at the ends of the lines, ambition parallels children, representing the age-old question for women as an either/or decision. “Now, thinking about being a woman in my thirties and the future, I suddenly feel this tearing of my identity and my desires,” Florence Welch said in a statement. ”That to be a performer, but also to want a family might not be as simple for me as it is for my male counterparts.” In the chorus, Welch rejects marriage and family, but also female gender roles: “I am no mother, I am no bride, I am King.” The use of the masculine title “King” alludes to how men – specifically the male artists Welch mentions – don’t have to contend with this choice.

But it’s not a simple decision by any means. Welch sings, “a woman is a changeling / Always shifting shape / Just when you think you have it figured out / Something new begins to take,” explaining that the act of picking one over the other is complicated by evolving goals. “The whole crux of the song is that you’re torn between the two,” Welch told Vogue. “The thing I’ve always been sure of is my work, but I do start to feel this shifting of priorities.”

‘Dance Fever’ also delves into the roles ascribed to women, especially on ‘Dream Girl Evil.’ Welch explores how those archetypes are built specifically from the male perspective, playing into male desires: “Am I your dream girl? / You think of me in bed.” She goes on to say this is an unrealistic, essentially imagined ideal: “But you could never hold me / You like me better in your head.”

She further illustrates how men seek to define women through their relationship with them in the lines: “Did I disappoint you? / Did mummy make you sad? / Do I just remind you / Of every girl that made you mad?” These lines demonstrate the fragility of these caricatures, and how women are lumped together and stereotyped. Ultimately these are all false personas ascribed to women when they fail to meet the impossible expectations for women: “Make me perfect, make me your fantasy.”

Nova Twins’ ‘Fire & Ice’ also challenges these one-dimensional portrayals of women, starting by pushing back against being “good” in the lines: “I don’t want to play nice,” and “I am the sinner, I ain’t the saint.” Vocalist Amy Love sings, “I can be tough / I’m volatile, don’t want to smile or cheer the fuck up,” stepping outside of gendered impressions – and referencing sexist comments. The chorus mentions “sad girls” and “bad girls” – reclaiming two female archetypes – before ultimately declaring, “I’m the villain that you like.”

But it’s also about dualism. As the refrain, “I can be the fire and ice,” expresses, not only is the speaker more than one thing, but she embodies two opposing extremes. Love illustrates the capacities for both help and harm in the lines, “I’m the tightrope / That will take you to safety / Or wrap ’round your neck ‘till you choke,” with the tightrope’s precariousness underscoring how easy it is to transform. And it earns strong reactions in both directions: “I am that bitch that you love and you hate.”

“People assume that we’re scary or we’re this and that, but we’re all those things and the opposite,” Love said. “As women, we’re never just one thing; we can be moody, upset, loving, happy, vulnerable, sweet. It’s just about being a normal girl today—it’s not always pretty, but that duality is always going to be something you love about us.”

In talking about her own song, Love summed up how all of these artists present more detailed and multi-faceted accounts of women and their experiences through their work. It’s their roles as artists – rockstars – that allow them to present themselves authentically and fully, in all their complexities.

It may seem like great strides are being made when it comes to sexism in the music industry but in speaking out through their art, these artists are highlighting just how pervasive it still is, in music and everywhere else. For their thousands of young female listeners, hearing the rejection of these established narratives will help to ensure that a new generation won’t define themselves by others’ expectations and as Florence Welch so rightly said, when the patriarchy finally starts to be dismantled, “You’ll be sorry that you messed with us“.