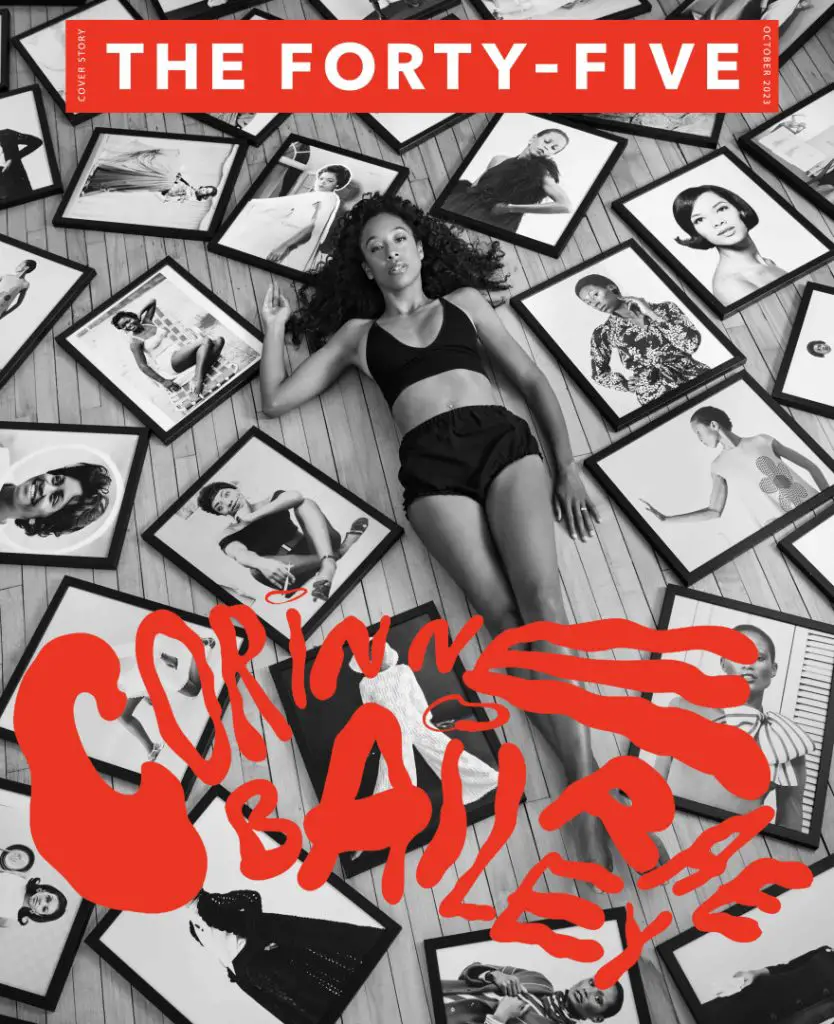

Corinne Bailey Rae

Corinne Bailey Rae no longer cares about writing a hit. But with this new-found freedom has come some of her most exhilarating and powerful work to date. Lisa Wright meets an artist reborn.

On a September evening in Harlem, 86-year-old Audrey Smaltz is standing on stage at the National Jazz Museum, giving the crowd a small window into her storied past. A celebrated model and fashion industry pioneer, she was a contributing editor to Vogue and, in her sixties, went on her first ever date with a woman and married her soon after. Smaltz’s life, all in all, has not been a boring one, but on this particular night, she’s toasting a new achievement to add to her sizeable list of them.

“I got her up on stage and she talked a bit, and then she said, ‘I’m so grateful to be here and now let us all enjoy Corinne’s unusual music…’” chuckles Corinne Bailey Rae, the ringmaster of the evening’s festivities.

‘New York Transit Queen’ – the lead track from Bailey Rae’s latest album ‘Black Rainbows’ – is notable not just because it eulogises Smaltz via a photograph taken in 1954, when Smaltz won the Miss New York Transit pageant, but because, for anyone familiar with the singer’s previous work, it is, indeed, unusual music. A riot grrl blitz of hand claps and blistering guitars, it’s an electric cut that has more in common with Yeah Yeah Yeahs’ incendiary ‘Fever To Tell’ era than the mid-tempo singer best known for telling the world to put their records on. And, in the grand spectrum of ‘Black Rainbows’ as a whole, it’s only just the start.

Across the game-changing record, Bailey Rae goes from futuristic robo-pop on ‘Earthlings’ to vitriolic rage on ‘Erasure’; the eight-and-a-half minute ‘Put It Down’, meanwhile, moves through transcendental neo-soul to a throbbing dance pulse. Throughout, the 44-year-old singer sounds enlivened and completely reborn. On aggregate site Album of the Year, it is the second highest rated from the whole of 2023 so far, with an average review score of 9.1 out of 10.

Undoubtedly, ‘Black Rainbows’ will live as the record that, 17 years after her debut, changed the Leeds singer’s career trajectory entirely. Which makes the fact that she initially deemed the album a commercially un-viable side project all the more telling.

“Having been on labels for a really long time, I’d definitely started to police my own ideas as I created,” Bailey Rae explains, Zooming in from a hotel room in Nashville, midway through tour. “I’d sit there and come up with something and I’d say, ‘Well there’s no point even finishing that because it’s not gonna be three minutes long, it doesn’t have a catchy chorus, it’s not gonna get played on the radio…’ I’d started to think like an A&R person.

“Having been on labels for a really long time, I’d definitely started to police my own ideas as I created. I started to think like an A&R person.”

Corinne Bailey Rae

“I think that [mainstream success] was definitely the expectation after the first record did so well – which was not what I imagined would happen because I saw it as an indie-soul record. And I was thrilled, and I got to fly in a private jet to Oprah and play at the GRAMMYs, and it opened the door. But it’s like that Coen Brothers film [The Ballad of Buster Scruggs] that’s about a musician in the ‘60s,” she continues. “He plays this beautiful ballad to a man for criticism, and it’s a magical moment, and then at the end the man just says: ‘I don’t hear money here’. And I got that response a few times where I’d have the beating heart of a song and they’d go, ‘Yeah it’s good but it’s not a single…’”

Bailey Rae recalls the process for 2016 third album ‘The Heart Speaks In Whispers’ being one where she “almost made several records and had a load of it rejected – either by the structure or by myself – before I’d even finished it”. An unsustainable path, when it came to starting her next work, she decided to think of it as something away from the constraints of what a Corinne Bailey Rae record ‘should’ be. “I think the side project [notion] was a good place to escape to because I thought, let me completely disregard all of those aims that I’ve been trying and failing to achieve and just MAKE,” she nods.

The catalyst for what would be made came when Bailey Rae discovered the Stony Island Arts Bank in Chicago. A broad and deep encyclopaedia of Black history, the building and its contents were a revelation like no other. Over the past seven years, she would visit as often as possible and describes feeling like “all roads lead back [there]”; “I just felt like it was speaking to me,” she says.

The bank comprises more than 26,000 Black literature books on every aspect of history and society dating back more than two hundred years, as well as vast collections of items both celebratory and problematic. There’s an entire vinyl collection from house music godfather Frankie Knuckles, but then 16,000 “derogatory objects, anti-Black propaganda stuff” that forms the Ed Williams collection – an attempt to remove the items from public circulation whilst also highlighting the generational depth of the issue.

“I’d read all the Black books in my school library and a good amount of them in my University, and I had wider questions, but when I spoke to other people they’d say it’s kind of oral tradition so it wasn’t written down,” Bailey Rae remembers. “Or they’d say those stories weren’t documented, or people weren’t literate or the documents had been lost. So I had this thought that so many of the things I’m interested in were just lost to history, and then to walk into this bank and see the volume of literature on these subjects… that just blew my mind.”

A keen researcher, the discovery not only whet the musician’s appetite on an intellectual level, it also finally started to redress the balance of Black representation (or the lack thereof) that she had encountered her whole life. “I remember school history books where there’d be two or three photographs [of Black people] in the book, and one might be Martin Luther King but the other one – I distinctly remember it – was the charred body of a victim of racial violence; someone who’d been lynched and set fire to,” she recalls. “I was 13 or 14 and this was in the school textbook. And I understand why it was in the book, but there was no sensitivity to the fact that there were Black children in the class, and also there was no balance.

“I describe [what was presented then] like a circus mirror,” she continues. “It’s white-imagined Blackness. But at the same time, as a Black person, there was so little visibly reflected back in the culture that you would – one would, I would – stare in that circus mirror to try and see my reflection.”

Across ‘Black Rainbows’, the wildly differing styles and sonic explorations are bolstered by lyrics that take their inspiration from the breadth of discoveries found within the Arts Bank – some joyful, some sad, some sweet, some full of rightful fury. “The fascination for me,” explains Bailey Rae, “was that you could bounce between these rooms, and when you wanted to come out and get air [from the traumatic elements] you could go into the library and be in Black academia, and then in Ebony magazine you could be back in a celebration of Blackness.”

On the mesmeric jazz of ‘He Will Follow You With His Eyes’, she riffs on the seductive promises of women’s magazine adverts, the track slowly morphing into a repeated mantra: “My Black skin gleaming / My Black hair kinking / My plum red lipstick”. There were other adverts in the collection that projected a wholly different image of Black womanhood, however.

“I always think adverts tell you so much more about culture than anything else because they’re presuming on a set of shared values. I remember adverts in the ‘80s and they were all so misogynistic – ones for Jif [bleach] that would be like, ‘Now you’ve cleaned the floor, what else can you do?’ with a wink to the camera,” Bailey Rae explains. “And similarly, these adverts from the ‘50s, there were so many that demonstrated Black women being used as household objects, that you had a housekeeper and they were as valuable to you as a fridge; there was no personhood.”

It’s this lack of humanity that fires through in ‘Erasure’, the most untamed explosion on the record. As images of “broken bones” and children being “fed to the alligators” swirl around heavy, growling thrums of guitar, Bailey Rae recalls the postcards depicting horrifically normalised violence that catalysed the track. “I’d look on the back of the postcards showing this racial violence, and they would say things like, ‘Dear Mum and Dad, just arrived in Georgia. I can smell the peach trees through the train window. Kiss Aunty so and so for me and pet the dog’. There was absolutely a disconnect between what was happening on the back of the postcard and the front because it was so normal.

“‘Erasure’ came out that way because it was so complex and shocking to be around the different kinds of erasures, and to see the impact of them,” she says. “The erasure of Black childhood. Black children not being seen as innocent and then, in the same plot as the Arts Bank, the Tamir Rice pavilion where he was shot by the police in 2014 – a young boy who was perceived as a dangerous weapon-carrying man, but who was just a child. I thought, there’s a link between 300 years of racist propaganda saying ‘Black children aren’t really children’ and then the actions of police officers on seeing this 14-year-old child. It was all this history, but it’s so corrosive and fizzing with contemporary issues, and that all came into ‘Erasure’ and made it sound the way it does.”

When will you do the things that challenge you, the things that make you feel afraid and the things that are brave? Why not now?”

Corinne Bailey Rae

So much research and thought and heart and history has gone into ‘Black Rainbows’, it’s quite incredible that Bailey Rae has managed to distil it all into what is, at base level, a sub-45 minute, 10-song record. It’s an album that rings with personal connection and truth; that’s instinctive and passionate and fuelled by everything the musician had previously denied herself the permission to be. On stage, she’s been preceding the tracks with information about the findings that led to their creation as an added window into the record. And now in her mid-forties, she’s a firm advocate for the power that comes with age. “Maybe it’s also being aware of how much time you have left – if not now, when?” she muses. “When will you do the things that challenge you, the things that make you feel afraid and the things that are brave? Why not now?”

To the outside world, ‘Black Rainbows’ is an album that has reset the image of Corinne Bailey Rae completely. More importantly, however, it’s done that for the musician herself, too. “I feel like the doors are open to me because I’m starting to think of myself as an artist instead of someone who’s trying to get a pop song. I’m thinking of myself in a different way, and now I do feel like, ‘What can I do next?’ I feel like I’m back in the playful mindset of music,” she smiles. “I feel really excited about everything now. I’ve opened it up and I can’t go back.”