A R L O

P A R K S

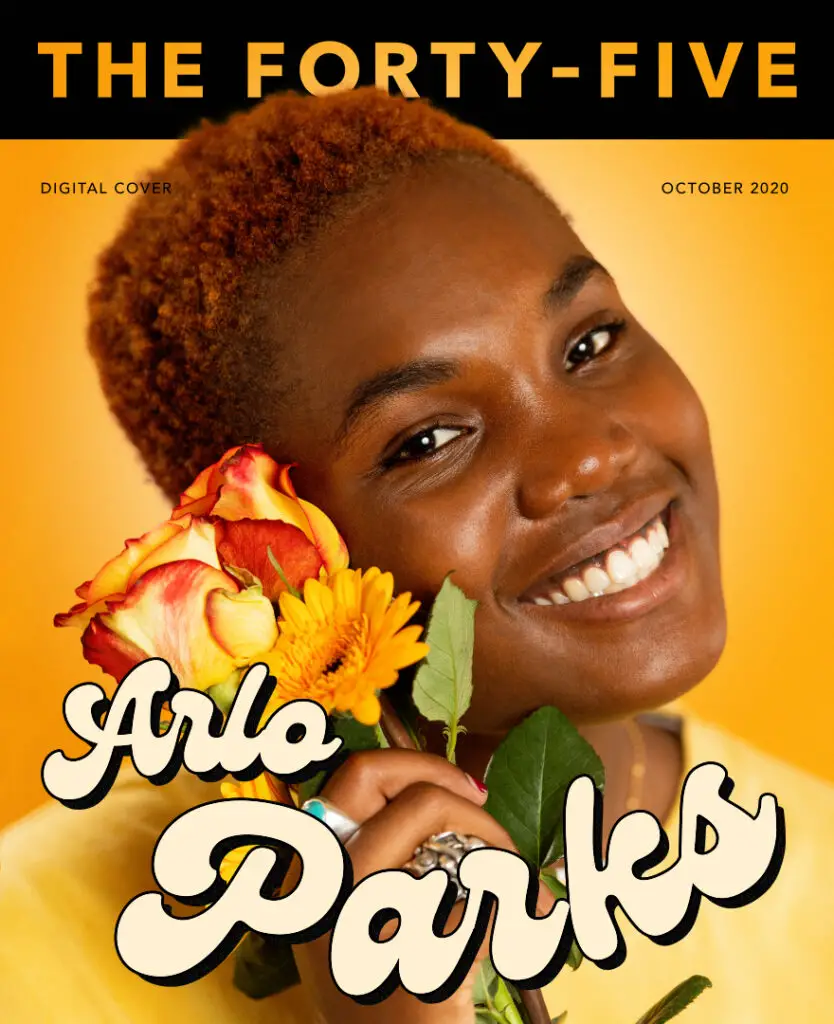

Arlo Parks is having one of those years – career wise – that every young artist can only dream of. From relative unknown, in these strangest of times her music has resonated with countless people trying to make sense of the world. El Hunt meets the musician for a chat about grief, connection and why she can’t wait to flail about on the dancefloor.

Photos: Sarah Louise Bennett.

What have you missed most in 2020? The jostling buzz of a gig, and being shoulder to shoulder in a low-ceilinged room? Sharing a lukewarm tinny on the sardine-like slow train to Glastonbury? Dancing in a packed basement full of strangers? Arlo Parks has been missing all of these things, but mainly, she’s been missing “dad-dancing”.

“I’ve had a fair few at home dance parties by myself,” the 20-year old musician says, slightly mournfully. It’s not the same, apparently. “Being completely ridiculous on stage is what I miss the most. Even if I take dance lessons I’ll do the dad moves on purpose. It’s all about not knowing what you’re doing, but you just don’t care what your limbs are doing,” she adds, offering a few pointers. “They’re all moving in different directions. Be playful. There’s no rules – just freedom and bad flexibility.”

A slightly “plane-frazzled” Parks arrived home from Milan just under an hour ago (she cracked out her finest high-fashion suit for the Valentino show) and now she’s chatting away beneath the sloped ceiling of her attic bedroom. The jet-setting is a relatively recent development owing to the coronavirus pandemic; otherwise, she’s been living a relatively quiet existence. “Most of this year has just been writing, reading old journals, and DJing techno in my room by myself. I got to do all the things that usually I don’t have time to do,” she says. Like cooking up constant Mexican feasts, for example. “Chicken fajitas, every day! Thinking about them now has made me so happy…”

The musician grew up in Hammersmith, West London – where she still lives now. Though none of her family are particularly musical, her home was a “a very safe, loving space” where her creative leanings were encouraged early on; an eclectic collection of records piped continuously around the house. “Miles Davis, Chet Baker, Thelonious Monk, a bit of Daft Punk, Otis Redding, Al Green,” she reels off. “My mum liked ‘80s French pop and Prince. And when I got my uncle’s record collection I discovered people like Bob Dylan, Sade, Robert Smith and the Stooges. All these people use their voices in different ways,” she says, wondering aloud whether the genreless mixing pot has influenced her own music. “It made me never overthink the way that I sang things.”

As a kid, Parks was both introspective, and endlessly fascinated by other people. “I’d just go up to people in the supermarket,” she laughs, “and be like ‘Hi, how are you? I like your coat!’” Often, she channeled this fascination into writing stories: “kind of like Lord of the Rings, and just very strange. There were some stories about highwaymen with superpowers,” she says. Over time, “that morphed into poetry. I’m quite a visual person. I was way more focused on the imagery than the plots.” After that, songwriting was a natural progression. “I see my songs like looking down the lens of a camera at a scene in a film, she explains. “In order to construct that scene completely for somebody who hasn’t seen it, I think including small details makes the scene feel more rich.” And open the door to Arlo Parks’ music – whether it’s the yearning ‘Eugene’ or the swooning ‘Angel Song’ – and these specific snippets are everywhere: open books of Sylvia Plath’s poetry, a fleeting mention of Courtney Love, or a T-shirt that makes someone look like My Chemical Romance’s Gerard Way.

I SEE MY SONGS LIKE LOOKING DOWN THE LENS OF A CAMERA AT A SCENE IN A FILM. INCLUDING SMALL DETAILS MAKES THE SCENE FEEL MORE RICH.

ARLO PARKS

And what was the first song Arlo Parks ever wrote? “I vaguely remember…” she winces. “I think it was about someone I had a crush on. I was a dramatic child, so I bet it was just like: ‘oh my god, I love you so much’. My process for writing has weirdly stayed the same since then, though,” she laughs. “I’m not sure if that’s good or bad!”

Since she first learned to talk, the musician has spoken both French and English fluently (her mum is half-French and grew up in Paris) and being bilingual, she reckons, has contributed to her own distinct voice. “In French music, there’s a lot of storytelling, and knowing French gave me a slightly more free approach to language. Maybe [because] I didn’t know the rules as well? Sometimes I think in French, and maybe that’s how I hone my voice to make something that feels quite unique.”

Thinking back to the songs which have affected her most deeply – Otis Redding’s (Sittin’ On) The Dock Of The Bay’ or King Krule’s haunting and Basquiat-namechecking song ‘‘Out Getting Ribs’ – she pinpoints the idea of “being moved by music and not really understanding what that meant, but wanting to elicit that feeling in someone else. I felt really strongly towards it, but I couldn’t put a name to it, I didn’t really understand. But I definitely felt like it was something I wanted to try myself.”

Arlo Parks’ music frequently deals in unravelling complex tangles; the sort of knotty feelings that press down on joy, leaving a dull ache in its place. The quietly obliterating ‘Black Dog’ arrived during this year’s most intensive period of coronavirus lockdown – at a time when meeting with other households was still banned – and its lyrical isolation spoke to the coincidental backdrop. And her most recent release ‘Hurt’ sets percussive grooves alongside the kind of chilling numbness that dwells inside the hole that permanent loss leaves behind. “Then his fingers find a bottle,” she sings, “when he starts to miss his mum.”

The musician depicts sadness and grief with such a raw precision that she often catches her listeners completely off guard. And it comes from knowing them both intimately: when Parks was seventeen, a friend took his own life. The loss, she explained in a candid Instagram post earlier this year, “came with a very specific kind of agony.’” The event shifted her entire perspective and purpose. “I decided then that my mission was to help people who were struggling in any way I could,” she wrote.

“[Experiencing grief] has made me very focused and aware of my mortality,” Parks expands today. “I’m determined to do positive work with the time that I have on this earth. I think it’s also made me practice gratitude in a more committed way. I’m determined to pursue what I love. It made me very aware of the limit of things,” she says, “and how quickly things can just be snatched away. I use it as positive fuel.”

EXPERIENCING GRIEF HAS MADE ME VERY FOCUSED AND AWARE OF MY MORTALITY. I’M DETERMINED TO DO POSITIVE WORK WITH THE TIME I HAVE ON THIS EARTH.

ARLO PARKS

Being a totally open book, she adds, and speaking honestly about issues such as depression and anxiety, is one such way that Parks channels her experiences into something that feels hopeful. And every time a person gets in touch to share their own story, she says – and the ways that her music resonates – it’s further proof that vulnerable art can make us all feel a little less alone.

“There are lots of topics that people tiptoe around because they feel uncomfortable,” Parks says, “but they are so common. Those are the ones in particular that I feel we should be speaking about.”

And such honesty is also a reflection of the music that Arlo Parks listened to growing up: “[thinking about] a lot of my favourite artists,” she ponders, “I love them because they express themselves in a way that feels completely genuine, and is generally quite emotional. I listen to different music for different reasons. I think that’s why when you’re thirteen you listen to My Chemical Romance or Good Charlotte, because they’re raging against everything and that’s kind of what you need at that moment.”

THERE ARE LOTS OF TOPICS THAT PEOPLE TIPTOE AROUND BECAUSE THEY FEEL UNCOMFORTABLE. THOSE ARE THE ONES IN PARTICULAR THAT I FEEL WE SHOULD BE SPEAKING ABOUT.

ARLO PARKS

Did she go through an emo phase, by any chance? “Not outwardly, but inwardly,” she smiles, before describing the sonic mess that awaited anybody scrolling through her iPod.

“It had some random jazz music, the Arctic Monkeys first album, and Fall Out Boy. I had the album with ‘Thanks For The Mmmrs’ [‘Infinity on High’] and I know all the lyrics,” she smiles proudly.

Practicing gratitude is an idea that Arlo Parks returns to often, and in trying to make sense of a surreal year in which her work has connected with more people than she ever dreamed possible, she tells herself that “this is amazing and unexpected but there’s still work to do”. Parks has been journaling almost every day – she’s finally committed after past diary-keeping efforts fizzled out after a few days – as a way of making sense of everything. And there’s a lot to grapple with in a year that began with being tipped by the BBC’s Sound of 2020, and just yesterday, took her to the surreal surroundings of Milan Fashion Week (“I was wearing a cape!” she grins). Just a couple of months ago, her song ‘Cola’ cropped up in Michaela Coel’s devastatingly brilliant TV show I May Destroy You. The series, which explored consent, anxiety and substance abuse with a dark and closely-examining wit, shares a few parallels with Parks’ own illuminating writing.

“Damn,” Parks remarks, “Michaela Coel is a force, she’s so incredible. I felt like that show was something that I needed – but I didn’t know I needed it until I watched it. That was one of those moments that felt quite surreal. It’s like, what’s happening?! I always have that moment of being quite confused. Having that recognition, and my music being shared a little more widely every day makes me feel warm, and like I’m doing something right. A lot of the creative process is about trusting your gut and hoping that it resonates,” she adds.

MICHAELA COEL IS A FORCE, SHE’S SO INCREDIBLE. I FELT LIKE THAT SHOW WAS SOMETHING THAT I NEEDED – BUT I DIDN’T KNOW I NEEDED IT UNTIL I WATCHED IT .

ARLO PARKS

These surreal moments seem to happen to Arlo Parks almost daily, but until recently they took place outside a bubble – the musician has spent a good chunk of this year hunkering down away from the world. At the start of this year, she began work on her forthcoming debut album, and when the entire country went into lockdown, Parks happened to be holed up with her long-time producer Luca Buccellati (also well-known for his spellbinding collaborations with Tei Shi). As the world shut down overnight, the pair decided to stay put.

“In times of chaos, I always go to music because that’s what I know,” Parks ponders. “It’s what I cling onto. I was in this Air BnB, working on music, when lockdown hit. We were in this bubble for weeks: not seeing anyone, going for one walk a day by the canal in Hackney, eating pizza…”

“It was an experience that will never happen to me again,” she points out. “Looking out onto the streets of Hoxton at 10pm on a Saturday night, and there’s not a soul. It made me feel like I had a purpose. I didn’t feel functionless. I had something to do, I was doing good work, and I think that’s what kept me stable. Weirdly, that sense of isolation and being in that bubble made me reach depths within myself that maybe I wouldn’t have been able to if I was in the normal world with distractions and other responsibilities. I was fully living inside my album, it was very immersive.”

Shortly after our conversation, The Forty-Five gets an early spin of Arlo Parks’ next single – a shuffling groove peppered with richly jazzy chimes, ’Green Eyes’ is eventually bound for the debut album. As far as break-up songs go, this is a deeply compassionate one. “Of course I know why we lasted two months, could not hold my hand in public, felt their eyes judging our love,” she sings softly, seeming to allude to queerphobia and unsolicited scowls from strangers. It’s a hollow reminder of the blossoming connections that get stifled every day by other people’s judgement: both sad, and surprisingly generous. “I could never blame you darling,” she reassures warmly. For anybody who’s ever snatched their hand away from somebody else and shoved it safely into their pocket just to avoid strangers’ comments, it rings painfully true.

And last month, Arlo Parks finished recording her album. Though she’s tight-lipped about when the world can hear it – ”I mean, I know, but it’s a secret,” she smirks – she’s visibly excited to unleash a time capsule from her rapid ascent. “It’s exciting and also terrifying,” Parks admits. “It’s the first time I’ve had this massive body of work, and put my name to it. It’s something I’ve spent a lot of time and tears on. Although I’m apprehensive, I’m really excited.”

That apprehension, she adds, is a sure indicator that she’s digging deep enough. “When I release a song like ‘Black Dog’, because it’s so close to the bone and a real story, there is that sense of fear as to how people will respond to it. But that uncomfortable feeling… that sense of slight discomfort or nerves… it makes me feel like I’m pushing the boundary in some small, subtle way,” she says, “and it’s something that’s close to my heart and meaningful.“

“I can’t remember who said it,” she remarks, “but I read that if you create a piece or art or music that has the potential to help someone else, then it’s your duty to put it out. That desire to help others outweighs the nerves, and that feeling of being exposed.”

And there’s no question that, by bearing the vulnerable and raw part of herself to the world, Arlo Parks is helping people. In a sense, she’s the voice that she would’ve loved to hear growing up. “I think hearing songs that directly resonated with my experiences would’ve made me feel quite held I think,” she concludes, “and less alone.”