While nineties nostalgia has never been more in vogue, the culture surrounding Britpop seems to have aged about as brilliantly as the running gags in ‘Friends’. It’s not just its associations with laddish attitudes and rockism, either: it’s about the way the movement celebrated a white-washed and often hackneyed version of Britishness, a fact which was unsettling enough back in the mid-nineties but which has since taken on an even more sinister significance post-Brexit.

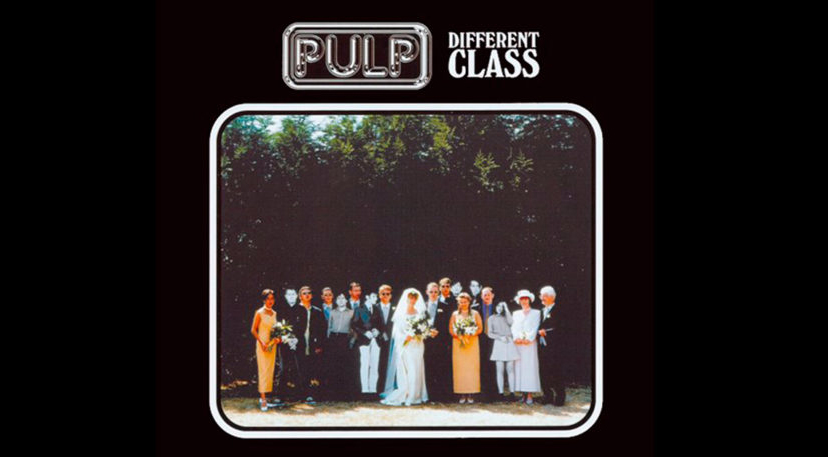

As the architects of ‘Different Class’ – their big commercial breakthrough, and one of the era’s defining records – Pulp might have been the unwitting posterboys (and girl) for Britpop, but you didn’t have to drill too deep into their songs to find they couldn’t be further removed from any jingoistic bluster. Out of three of the album’s four top 10 singles, ‘Common People’ skewered class tourism, ‘Disco 2000’ dealt with unrequited childhood crushes, and ‘Mis-shapes’ was an anti-establishment call to arms that arrived paired with double A-side ‘Sorted for Es and Whizz’, which paid tribute to the decade’s real defining counterculture: illegal raves. The other single was ‘Something Changed’, which found Jarvis Cocker putting his barbed wit to one side to write an uncharacteristically sweet love song that’s still as swoon-inducing today as it was back in 1995.

The singles are only part of the story, of course. The truth is, a quarter of a century on, ‘Different Class’ plays like a greatest hits from start to finish. As bassist Steve Mackey confirms, in Mark Sturdy’s Pulp biography ‘Truth and Beauty’, that’s no coincidence. “In late 1994 me and Jarvis had this concept, to make an LP that was 12 pop songs and every one could be a single.” Former-guitarist/violinist Russell Senior further clarifies, “I don’t think we sat down to write hit singles, to approach things commercially, but more artistically. I find pop music much more interesting and difficult to do than indie music.”

With their fifth album, Pulp made it look easy, even if the truth was it had taken the Sheffield-formed six-piece a good 17 years to get to that point. But then that slow ascent provides a large part of the record’s appeal. Take ‘I Spy’, for example, a theatrical, Scott Walker-esque epic which finds Cocker meting out revenge on middle class domesticity by shagging the neighbour’s wife: a song that brilliantly bitter and voyeuristic could only have been written by someone long-accustomed to existing below the radar of polite society. And listening to a lyric like, “Imagining a blue plaque / Above the place I first ever touched a girl’s chest,” you can trace a line directly to the similarly droll, observational style of Stuart Murdoch of Belle and Sebastian.

Much like its predecessor – 1994’s truly exquisite ‘His N Hers’ – sex dominates ‘Different Class’, both in the in the shape of seedy trysts (‘Underwear’, ‘I Spy’) and unplanned affairs (‘F.E.E.L.I.N.G. C.A.L.L.E.D. L.O.V.E.’, ‘Something Changed’). So too does social commentary, finding Cocker putting suburban malaise under the microscope, be that working deadend jobs and living for the weekend (‘Monday Morning’), sexless marriages (‘Live Bed Show’) or existing outside of the mainstream (‘Mis-Shapes’). These aren’t polemics but they are, by virtue of their honest portrayal of the working classes, innately political.

And 25 years on, in a country where the class divide has only deepened due to brutal austerity measures, and where people working in the arts are being actively encouraged by the Government to retrain, an establishment-bating battle cry like ‘Mis-shapes’ feels every bit as timely as it is timeless. Combine this with fearlessly inventive songwriting that ranges from semi-ambient, spoken-word epics (F.E.E.L.I.N.G. C.A.L.L.E.D. L.O.V.E.) to Casio-flecked, indie-disco staples (‘Common People’), and you have one of the most fearlessly idiosyncratic British pop albums of all-time. Turns out the clue was in the album title all along.